The fighter

Berjis Desai

We shall call her Hilla Ghadially, though her real name was quite catchy. Her unusual surname was derived from a minor city in the Philippines (resist googling, it is not relevant). She must be cursing us from some astral plane for not revealing her name, as she was quite proud of her life story. Her birth had horrified her lower middle class parents staying somewhere near Baria Vad which, compared to the snooty Seervai Vad, was a bit déclassé. Today she would be called an intersex person. Pre World War I, she was called names which are unprintable. Had Hilla chosen to live as a man, few would have guessed. However there was very much a woman within her and she preferred to live like one.

Hilla was sharp, smart and intelligent. Even as a child, she did not tolerate any oblique comments on her sexuality; quite a few boors had had their noses bloodied. Navsari soon realized that it was prudent to be respectful to her. She matriculated in the Gujarati medium from the local Tata Girls School with decent marks. However, her spoken and written Gujarati was excellent. When she died, rather young in her early 60s, she had written more than 20 booklets in Gujarati on diverse topics and penned several columns in Parsi Gujarati newspapers under a pen name. She wrote in what Parsis derisively called shuddha (pure) Gujarati. None could guess from her writing that she was not a Gujarati.

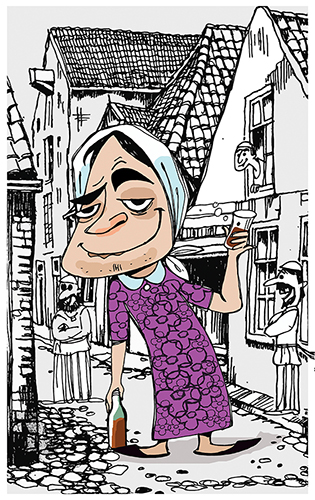

Illustration by Farzana Cooper

In the late 1930s, Parsis, in large numbers were drawn to Theosophy. Karma, reincarnation, vegetarianism, life after death attracted many. In Navsari, there was a prominent theosophist, one Ardeshir, who led a chaste and simple life, and converted many to the cause. Of course, the orthodox, barring the Ilm-e-Khshnoomists, thought the theosophists to be frauds. Hilla too came under the influence of Ardeshir and embraced Theosophy selectively. She abjured meat and even penned a treatise titled Jeevdaya ane maans khavani manai (Kindness to animals and prohibition on eating meat). Alcohol was a different matter. Prohibition in Mahatma Gandhi’s Gujarat did not deter her from guzzling desi or mahuvo (home distilled illicit hooch from mahua flowers); not surreptitiously, but while standing in the middle of the moholla wearing a gown reaching down to her ankles and offering a swig from the bottle to passersby. Theosophy and Ardeshir be damned. Once her insides were warmed, she boisterously joked and regaled her friends with bawdy stories.

If you had a problem, whatever be the time of day, Hilla Ghadially was there to help. Dressed in her trademark gown, when she spoke in a gruff voice, many were startled. Quick tempered, no-nonsense, but helpful. She ran errands for the rich and fixed things here and there, to feed herself and her two spinster sisters. She had a hearty appetite and was a perennial feature at weddings and navjotes. However, if one dared to insinuate anything about her gender, she was unsparing. She swore fluently with a lot of imagination rather than mechanically spouting boring abuse. Her decent literary flair must have helped.

She vibrantly moved throughout the day in the mohollas. Chatting with the women sitting on their haunches and selling vegetables; walloping a complimentary ice cream scoop at the Kolah shop in the bazar; checking the well-being of the visiting beggars ("Why have you come on a Monday? Today is Jamna’s day!”); walking up to the Kapadia no Bungalow, a public hall with a prominent watch tower for wedding feasts and conversing with the caterer’s men cooking food; fetching medicine from the dispensary for the sick; bantering with the men in the evening over several glasses of her favorite tipple, with the passing police jamadar saluting her.

At night, she wrote her books and columns and posted them to Bombay, a city she seldom visited. Contrary to her libertarian personality, her books were on sombre topics — purpose of existence; death and principles of reincarnation; solace for those missing their departed; and, like Jane Austen, a spinster, on the secret of a good marriage and happy family life. She unapologetically plagiarized from popular Gujarati authors, though she always rearranged thoughts in her own inimitable style.

When politics heated up after the state of Bombay was split into Maharashtra and Gujarat, she waxed eloquent to all who cared to listen, on the reorganization of the state. In the late 1960s, the Congress split into what popularly came to be called the Syndicate led by Morarji Desai whom she hated like many others in Navsari, and Indicate led by Indira Gandhi whom she adored and also met during Indira’s visit to Baroda. Municipal elections in Navsari were hotly contested by these two factions. One evening, somebody taunted her about why she did not plunge into politics instead of lecturing on it every day. She took the challenge seriously and managed to get a ticket from the Indicate faction. A popular, senior Congress lawyer was the hot favorite to win the election. Hilla was hardly deterred. When she actually filed her nomination, Navsari was taken by storm. An intersex person against an established lawyer! A battle royale, indeed. Sixty years ago, this was radical stuff.

When the opposition realized that she was serious and meant business, decency was thrown to the winds. Political correctness was an alien concept. Local newspapers and pamphlets brazenly commented on her sexuality. For the first time in her life, she was hurt. A street drunkard openly flouting the laws of prohibition cannot be a public representative, they contended. Stainless steel utensils and saris were distributed on the eve of election day. Poor Hilla Ghadially had neither the money nor the inclination for bribery.

Those were the days of manual voting; when counting began immediately after the close of polling. Losing was certain; however, whether she would forfeit her deposit was the question. She fervently prayed to Ahura Mazda, "I don’t mind losing but let me put up a creditable performance,” on behalf of all the poor, and the differently abled, and those whose gender was cruelly mocked, and the simple and the uncomplicated. Of course, the ladies selling spinach and the infirm whom she had served personally, trudged to the polling booth and voted. As the evening progressed, a chastised opposition realized that she had put up a surprising show. At dawn, with a margin of 67 votes, Hilla Ghadially became the first intersex municipal corporator of Gujarat.

She was uncomfortable with newspaper headlines and public meetings. She was now a celebrity in dull Navsari. Parsis did not felicitate her though the community media ran the story. Nothing much changed in her routine of walking with a glass of hooch in the streets; however, her faith in the Lord increased. Soon thereafter, alcohol, like always, extracted its price. She became seriously ill with liver cirrhosis and nearly perished. After a long battle, she recovered and published the best little book she ever wrote, History of the Navsari Atashbehram. Well researched, with acknowledged citations from historical texts, dissection of the ecclesiastical disputes between Sanjan mobeds who did not want the consecration of the new Atash Behram in what they perceived to be competition to the Iranshah, and first-hand accounts about the enthronement of the holy fire, the book sold like hot cakes.

Although she gave up the bottle, the disease and lack of nutrition eroded her former robust, feisty self. She remained indoors and smiled sadly at her many visitors including the old lawyer whom she had defeated in that memorable election who profusely apologized for having called her names during the campaign.

Berjis Desai, author of Oh! Those Parsis and The Bawaji, occasionally practices law.