The hen and the fox

Berjis Desai

He was so meek and mild that they called him Minoo Murghi (hen). Soft-spoken to the point of being inaudible, the notoriously rough students of the Tata Boys’ School gave their history teacher a lot of grief. Minoo though was a picture of equanimity in his unchanging dress of black coat, white trousers and a black cap set firmly on his head. Murghi’s wife was even more docile, seldom lifting her head from the jantar (wooden contraption for weaving kustis) while speaking to strangers. These docility chromosomes resulted in a super docile son named Rusi, who was partially deaf and had a magical smile, and a smart daughter, Ruti, who would soon be exported to Cape Town in South Africa to marry a Parsi spice merchant’s son whom she had never met or spoken to. Some poor have the right kind of self-respect, which Minoo’s family had.

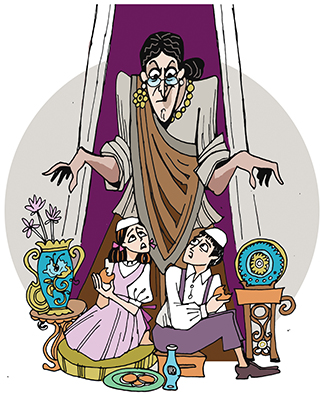

Genetics is a funny science. Minoo Murghi had a sister two years his senior, whom we shall call Mehra but Seervai Vad called her a Sly Fox (luchu shial). There was something very cold about Mehra; her expression resembled that of a security guard at a high security prison. She spoke little through her thin, pursed lips and her eyes were constantly mocking. If the good doctor next door had penile agenesis, Mehra’s sexuality was also ambiguous. Some said she was a transgender; others said she had no interest in men. Not that any man would have dared to give her an amorous look. Minoo and his family, of course, were mortally scared of Mehra.

Illustration by Farzana Cooper

While Minoo resided in a dark house from where seldom did any sound emanate and monotonously ate dar chaval né rotli with some roasted papad as a rare delicacy, and wore darned clothes, Mehra lived in a bungalow with huge wrought iron gates, on the edge of Seervai Vad. She had a retinue of Adivasi servants from the thicket behind who kept the many Chinese vases and antiques spic and span. Mehra could afford to throw a feast for the whole of Seervai Vad every day, but she ate little due to her chronic constipation, which was a psychosomatic condition in keeping with her refrigerated personality. When she was 12, she had been adopted by a childless Parsi couple who had made a fortune serving one of the maharajas in Kathiawad. Mehra’s biological parents living in abject poverty were told by Richie Rich that their daughter would bear his surname and have absolutely no contact with her family of birth, privately or in public. Most young girls would have been traumatized by this condition, but Mehra was simply delighted. Of course, she did attend the funerals of her parents which involved stepping out of the bungalow and sitting in one of the sedan chairs placed all over Seervai Vad, which was sealed off to prevent juddin entry. Her adopted parents too departed soon, leaving her as the only inheritor of a substantial fortune. If a visitor from Bombay happened to ask whether she was Minoo Murghi’s sister, she would just stare out of her many windowed palace, stirring tea in a bone china cup with a silver spoon.

The solitary exception to this no-contact rule was a visit by Rusi and Ruti on Vahishtoisht Gatha (Pateti), to greet their affluent aunt. The children eagerly looked forward to the tiny cupcake and a lemonade from Kolahs in a thick glass bottle (later used as a Molotov cocktail during communal riots) whose top was sealed with a marble that had to be pushed down forcibly by means of a small contraption. Of course, the lemonade had to be shared, as otherwise it may have resulted in deficit financing in Mehra’s annual budget. On one occasion, Rusi managed to wallop an extra cupcake which did not go unnoticed by the eagle eye of the Fox, who rose slowly from her chair and slapped the deaf child on his cheek. Ruti told her mother that the slap was so hard that she thought it would render Rusi deaf in the other ear as well. From that day onwards, this annual visit was discontinued.

Sometimes the cosmic uses the evil to bring about good. The Fox unilaterally decided to arrange Ruti’s marriage to the son of one of her acquaintances in South Africa. He turned out to be an ideal husband providing a fairy tale existence to his young bride from the backwaters of Navsari.

Mehra was soon elected chairperson of numerous charity trusts in Navsari and treated the beneficiaries with her trademark arrogance. She had no lovers, no friends, no relatives, no family; even the servants cowered before their cruel employer. Of course, she diligently attended to all the trust affairs and the management of her wealth with meticulous attention to detail. She was seldom seen praying at the Navsari Atash Behram. At dusk, when the poor electricity supply of Navsari dimmed the lights of the many lamps and chandeliers, she listened to the news on an old Murphy radio which she promptly switched off as soon as any music was played.

Even after the departure of Mehra’s adoptive parents, Minoo Murghi was never permitted to enter the bungalow. His sister, however, merrily sauntered into Minoo’s home without notice and found fault with a million things. Never did Rusi or his parents ever protest at this intrusion. Mehra confessed to a young Parsi doctor who practiced in Malesar, far away from Seervai Vad (the grumpy local doctor would not speak to her on account of her behavior towards her poor brother), that she found the family’s refusal to get provoked very infuriating and it was a means of silently mocking her. Mehra would have died a thousand deaths if she had heard the men in Seervai Vad, inebriated after drinking toddy, discuss her non-existent sex life.

Polite smiles did not prevent the collective hatred of Seervai Vad from radiating through to Mehra. Even Makimai Khokhru, the neighborhood’s loudmouth, desisted from conversing with her. Mehra decided to adopt the young doctor and his nuclear family from Malesar. She was confident that Minoo would protest strongly at Rusi and Ruti being bypassed. He did not.

Not satiated with the antique jewelry inherited by her from the adoptive parents and their childless siblings, the Fox began preying on the old and the lonely. Pretending to look after them, she spirited away grandfather clocks, vases and English heritage crockery. Her kleptomania became known and the residents of Seervai Vad soon cast aside the veneer of civility in their interactions with her.

Angry and isolated, in order to cock a snook at all, she invited the young doctor and his wife to move in with her in the bungalow and registered a will bequeathing everything to them. She soon discovered that the "sweet” doctor was no Minoo Murghi but Ivan the Terrible, and his aggressive wife was viciousness personified. Mehra could not believe the transformation of her adopted children. She summoned them and spewed fire and brimstone. No one in Navsari had ever argued with her. The doctor walked up to Mehra and, without uttering a word, slapped her hard on the face. Her spectacles broke and she crumpled on the floor. Unwisely, she threatened to change her will.

Mehra the Fox spent her last seven years locked up in a small room near the attic overlooking the thicket from where the children of her abused Adivasi servants called her unmentionable names. Strangely, her constipation disappeared and she developed a hearty appetite, which remained unsatisfied on most days. Minoo Murghi made a feeble attempt to see her and was warned that his legs would be broken. No one complained to the police or moved the courts to secure Mehra’s release. The grumpy doctor momentarily contemplated intervening but was dissuaded by others. In the meanwhile, Rusi married a sweet, poor girl and had two boys; and when Ruti occasionally descended on Navsari, Minoo’s little household reverberated with happiness.

One afternoon, Mehra heard a great commotion. The doctor and his wife appeared to be celebrating the anniversary of World War II by hurling her priceless English crockery at each other. Stunned servants watched in horror as plates and dinner sets were smashed. A crowd gathered and Seervai Vad was treated to some high quality entertainment. When a smile flickered on Rusi’s face, Minoo Murghi, the history teacher, castigated him, "She is our blood.”

Berjis Desai, author of Oh! Those Parsis and The Bawaji, occasionally practices law.