James and Elizabeth

Berjis Desai

During her long life of over 90, she must have used at least a tonne of cosmetics. Gaudy orange lipsticks, countless tins of Pond’s talcum powder, hundreds of eye darkeners, mascara for her non existent eye lashes, unlimited pouring of Tata’s Eau de Cologne on her large body. Of course, nothing fancy or expensive. Her salary as a school teacher in a Parsi charity girls’ school (she was too lazy to give private tuitions) and her husband’s head clerk salary in a large Parsi conglomerate, were just enough to support their, rather her, lifestyle. Being childless helped. She always wanted to look good. So what if she had wrestler arms, a mouth large enough to swallow a pomfret, skimpy hair always dyed jet black, and oodles of fat tightly packed in a corset with ill-fitting blouses and then wrapped in loudly colored saris. Such a body naturally required lots of paint and gloss. "When I die,” she instructed her nieces, "please ensure that you apply proper makeup to my face along with my favorite red lipstick. I hate looking shabby to those doing sejdo (final obeisance) to my body.”

She was nearly born in her native Navsari, instead of Nagpur, where her father had landed a job with Tata’s Empress Cotton Mills. She thereby nearly missed being schooled in the Gujarati medium girls school, and instead, managed to speak good English from the St Joseph’s Girls Convent, Nagpur. This made her feel superior to her many country bumpkin cousins, who were ill at ease in spoken English, at home. ("Amy and Sorab don’t like to socialize, as they can converse only in Gujarati!”) An arranged marriage followed with a distant cousin called Jamshed. "My James and I,” she would confide to a rather shocked gaggle of senior school girls, "have never had sex, since our honeymoon.” But, I insist that he addresses me as Elizabeth, as I hate my name, Ala,” she informed.

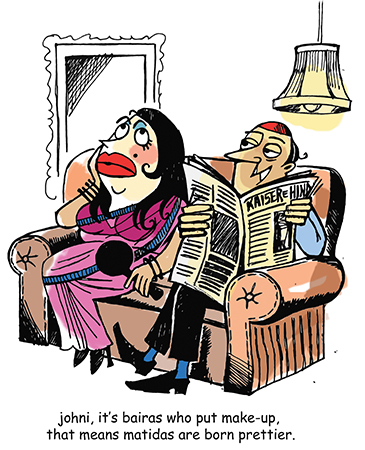

Illustration by Farzana Cooper

Elizabeth was loquacious, gregarious and loud. James was shy, insipid and dull. She talked incessantly; he seldom spoke. He stared passively at the wall when she talked and talked until she went breathless and choked on her own words. He let slip an occasional smile, her laughter was a strange cocktail of a chortle and a cackle (it emanated from the throat and sounded like a defective toy machine gun). In his early 50s, James complained of a hearing loss. Two eminent ENT (ear, nose, throat) surgeons concluded that there was nothing physiologically wrong. Perhaps, it was a psychosomatic reaction, a defence mechanism against a non-stop barrage of words coming out of her, at great velocity like a teleprinter of the old days, gone berserk. In his later, years, he went stone deaf ["Béhra né béhésht (the deaf are always in a heavenly state),” he said]. Even though Elizabeth knew that he could not hear her, she continued her monolog, in the same breathless fashion.

Most of the conversation was around the state of her health. In days when annual medical checkups were unknown, she marched, every month, to The B. D. Petit Parsee General Hospital, to have her sugar tested. As soon as her fasting blood sample was taken, she marched back to her tiny flat, a stone’s throw from the Hospital, where she consumed two large portions of papeta par eedu (eggs on potatoes), four ghee ni gagarti (dripping with ghee) rotlis, a quarter kilo of Parsi Dairy’s malai barfi, a generous carving of Edam cheese – washed down by syrupy sweet cups of milky tea. The disparity between her two readings (fasting and postprandial) invariably shocked her GP (general practitioner, himself in his 80s) to pronounce her diabetic, which pleased her immensely. "My heart is constantly enlarging,” she complained for nearly half a century, to all those ready to listen to the intimate details of her medical history.

While most mocked her for being shallow and verbose, one bachelor friend of James (we will call him KP) listened to her with rapt attention. Tall, loud mouthed, and having giant hands, he escorted Elizabeth to plays, clubs, concerts; all of which James had little interest in. KP taught Elizabeth ballroom dancing and entertained her during the hot and sultry afternoons of the long summer breaks from school. Whether their relationship remained purely platonic was a matter of much debate in the mohollas of Navsari, where she condescended to pay a visit annually with her entourage — cutely called paronas — in the old Gujarati dialect.

This entourage included another of her admirers, a bachelor stockbroker of the Bombay Stock Exchange, much revered for his integrity. He quietly paid for her daily club visits as also the couple’s annual vacation in the hills of Northern India. Apart from being an Elizabeth devotee for her felicity to formulate sentences so quickly, he owned a string of thoroughbred fillies which sprinted equally quickly at the Mahalaxmi race course. He was secretly envious of KP’s closeness to her but was too polite to make his intentions obvious. When he was dying after a sudden stroke, she visited him in the hospital but he stared blankly at her and kept repeating the word, Nilambari. Elizabeth was for once tongue tied, as his faithful ganga (house help) and his prize winning horse were both called Nilambari.

After the hospital visit she rushed to the club to breathlessly inform her friends that: "He kept on repeating — Nilambari, Nilambari, Nilambari, Nilambari — and his sister, Pervin, was very embarrassed, and kept on explaining to all that he was referring to his horse, and not to the ganga; whereupon, I told Pervin that why do you keep explaining this to all and sundry including his ward boy in the hospital, and Pervin said that it is not nice for a man in his dying moments to be so feverishly remembering his ganga, however faithful she was! I told Pervin that after he is no more, I am ready to provide a job to his ganga, but I cannot do anything with his horse…”

Elizabeth’s ever enlarging heart continued to beat robustly. She outlived James, KP, her doctors, Nilambari, and one of her nieces. However, in the final months her lungs became progressively weaker. With great difficulty, she could even formulate a sentence; almost inaudible, and finally was reduced to a bare whisper. Every day, at dusk, she feebly applied lipstick and rouge to her emaciated cheeks, just in case that sejdo were to happen the next morning.

Berjis M. Desai is a lawyer in private practice and a part-time writer. He considers himself an unsuccessful community activist.