The doctor

Bejis Desai

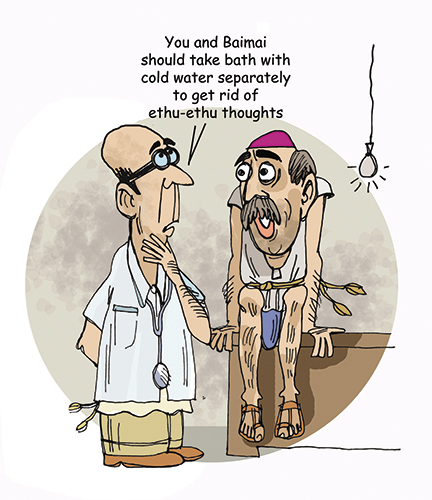

The general practitioner who was slapped by Hirabai, or whatever entity had possessed her (see "The hug,” Navsari Tales, Parsiana, January 21-February 6, 2020), was a popular figure not only in Seervai Vad but throughout Navsari. Considering that he had cleared his final MBBS only at the fourth attempt from the Grant Medical College in Bombay, the doctor placed more faith in Ahura Mazda, His Ameshaspands and Yazads than his own expertise for healing his patients. In keeping with this, he daily spent a couple of hours praying. His day began early at 5 a.m., when he bathed in ice cold water (even during chilly Navsari winters), a practice he strongly recommended to his male patients who wished to abstain from sex or what the good doctor termed as "bad thoughts.” Rumor though had it that he and his two elder brothers were born with an extremely rare genetic disorder called penile agenesis (in lay terms, born without a penis).

After thus purifying himself, he recited the Hoshbaam prayer (which can only be intoned at Bamdaad or dawn). The doctor stepped out on the Romeo and Juliet balcony of his narrow two-storeyed house in Seervai Vad to check if there was jajakloo (the first strands of light were visible in the sky) to begin this prayer. Thereafter, he pored over a huge copy of the Khordeh Avesta through thick rimmed glasses to correct his highly myopic vision. Of course, he knew most of the prayers by heart; nevertheless he always read them, to ensure that his thoughts did not wander.

Illustration by Farzana Cooper

After having thus procured divine assistance, he sterilized his syringes, needles and scissors in hot water in a large tapeli and placed them carefully in a huge brown leather bag which he lugged along with him the entire day during his many visits to patients. He cooked his unchanging breakfast of milky porridge in the same tapeli. Of course, the syringe and needle were used throughout the day on multiple patients. The doctor had a bhaari hath (heavy hand) and those injected yelped in pain, which greatly irritated the doctor who vigorously rubbed the affected area with the same cotton swab dipped in surgical spirit.

He always wore white — a loose cotton bush shirt reaching down to his knees and rough duck cloth trousers, which were washed weekly. Sometimes he wore a white jacket with a rust colored crumpled tie, the only one he possessed. For some strange reason, he never attended weddings and navjotes, even those taking place in Seervai Vad. Lagan nu bhonu would be delivered to him, which he ate silently by himself in the kitchen; a diehard introvert. The mean, however, said that he was too miserly to give a pehraamni (cash gift). He never missed a single paidust or uthamna though (again, the uncharitable said to prevent mourners from attributing the cause of death to him).

Most of his patients were too poor to pay even the one rupee he charged as visiting fees. He served them free, for decades. He injected vitamin B12 into those who were malnourished, using the free physician’s sample he got from his brother who was the principal distributor of Cipla medicines in Navsari, Surat and Bharuch. Poverty always moved him and he often quietly tucked a couple of rupees under the patient’s pillow to enable them to drink milk and eat well. He never charged practicing mobeds or their widows. Of course, all services to Seervai Vad residents were complimentary.

After a spartan lunch of rice, dal, and occasionally fish sent by some grateful patient, he enjoyed a brief siesta and then sat in his Baby Hindustan car, driven by Abdul who talked non-stop to his employer who would be dozing in the back seat until they reached the ramshackle dispensary opposite the Navsari railway station.

The doctor grumpily surveyed his dispensary overflowing with patients. Small children would be merrily urinating under rickety wooden chairs and crying in unison out of collective fear of the medicine man. Each patient had been given a token with a number which was called out aloud by an extremely short compounder who sat on a tall stool and mixed the medicines. After examining the patient rather cursorily, the doctor would shout a command to the compounder — taap né khaansi (fever and cough) or pét bandh karvaani (diarrhoea) or kabajiyaat (constipation), and the latter would hand over a bottle containing a suitable "mixture” with pre-marked dosages. The compounder often made mistakes in understanding and implementing the doctor’s commands. No patient ever complained though, and the system worked seamlessly. Penicillin had not yet made its appearance in Navsari. A persistent fever or serious infection was treated with application of cold water sponges on the forehead and the back of the neck. The short compounder himself produced a concoction made out of garlic, dry ginger, turmeric and cinnamon, whose effectiveness was attested to by generations of grateful patients. The overconfident compounder often overruled the doctor’s commands and prescriptions. The patients were blissfully unaware of this and their faith in the doctor never wavered.

At the stroke of six, the dispensary was locked and Abdul drove the doctor to a small orchard in the Lunsikui area of Navsari which was his ancestral property where coconut, mango, papaya and chikoo trees grew. A long wooden table stood in the compound with a dozen wooden chairs, all occupied by the doctor’s friends who eagerly waited for his car to enter the orchard. It was a motley bunch. An obese man called Eruch with a pock-marked face who always wore a brown duglo (coat) with a tattered collar. A man nicknamed Bai bai karasyo (a tale for the future) whose coarse language was frowned upon by the doctor. An old man named Burjorji, with a pronounced limp, poured readymade tea from a huge aluminum kettle into small glasses and gave each member of the Lunsikui Club a large batasa biscuit to dunk into the glass, to be rescued later with a spoon and walloped in one gulp. The conversation was mostly inane. The doctor sat glumly and seldom participated or even smiled. It was a ritual nevertheless, until it was 7:30 p.m., when the doctor sat next to Abdul and several of his friends were packed like sardines on the back seat. The younger ones walked or cycled, as large and fat black sparrows called devchakli returned to their nests in a final burst of cacophony.

The car entered Seervai Vad punctually, making a great noise; children playing in the moholla ended their game, and the adult residents timed their dinner with its entry [Chalo! Chalo! Daactur ni gaari bi aavi gai, jaldi bhonu kahro! (Come on, come on! The doctor’s car has come. Take out dinner fast)]. The doctor prayed again for an hour or so, browsed through the previous day’s Jamé, ate some khichdi, drank a glass of warm milk and climbed up two storeys to plonk himself on the bed in the room he shared with his brother.

Berjis Desai, author of Oh! Those Parsis and The Bawaji, occasionally practices law