The joker

Berjis Desai

Awaiting his turn to speak at a meeting to mourn a nondescript Parsi called Sorabji, he was dreadfully bored. A pompous lady was next in line to deliver her eulogy. "Shera,” he whispered in her ear, "Sorabji used to regularly pee in the Willingdon Club swimming pool.” The lady stood to speak and loudly guffawed, much to the consternation of the stunned audience. She pretended as if she was choked with emotion to conceal her laughter. When she resumed her seat, she told him, "You are simply disgusting. Is this the time to crack one of your silly jokes?” He strode to the mike, and after a few cursory comments about Sorabji’s impeccable integrity, had the temerity to narrate Sorabji’s swimming pool indiscretion, leaving Shera speechless.

Being the only child of doting parents restricted his world view. Wags would later uncharitably remark that he was so self-obsessed that when he was at a wedding, he wanted to be the bridegroom; and at a paidust (funeral) he wanted to be the corpse.

He was bright enough to qualify as a solicitor, at first attempt, and rise to be a partner at an antiquated law firm, in his late 30s. He had to butter a particularly unpleasant senior partner to achieve this early elevation. Soon after he was confirmed as partner, he began to narrate stories about his senior, in his inimitable style. He claimed when the senior was an assistant in the firm, he walked up to his Scottish managing partner and informed him that he was leaving the firm, to accept judgeship of the Bombay City Civil Court. Just after India’s independence, this judgeship carried great weight. The Scot instantly made the senior a partner. Our friend would then tell his listeners that the truth was that the senior had not been offered any such judgeship, but only the post of Superintendent of Stamps, adding that the senior would, of course, have made an excellent Superintendent of Stamps.

Another story about his senior which he never tired of telling went thus: His senior, a bumbling giant, exhausted standing behind an eminent counsel arguing before a full bench of the Bombay High Court, decided to emulate the worthy counsel who had placed one leg on a chair. Apparently, the senior suffered from hydrocele (accumulation of fluid in the testicles) and one of the judges who simply could not bear the unseemly sight, rudely ordering the senior to stand straight, much to the delight of his sniggering juniors.

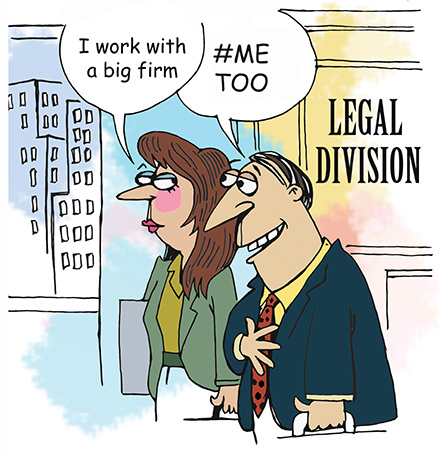

Illustration by Farzana Cooper

Our hero smartly identified a then nascent area of tax law to specialize, which made him a much sought after lawyer in corporate circles. With his wit, repartee and a slightly overdeveloped sense of humor, he managed to be the topmost practitioner in the field. As a student and a young lawyer, he worked quite hard, lest he suffer the fate of his solicitor father who had messed up his practice. However, after reaching the pinnacle of his career, he took things easy. Waking up after 10 a.m., he would trudge into office around noon, and immediately begin to devour a huge lunch his mother sent him, almost always wrapped up with overripe melon which would smell to high heaven, much to the disgust of his many juniors, mostly Parsis. Half an hour would then be spent on reading the Evening News, an eveninger tabloid from the Times Group. Anxious clients would patiently wait in the reception. A South Indian gentleman visited him almost daily on behalf of a large client, which irritated our hero. The man suffered from acute piles and was unable to sit for long. He would then get up and walk around the lawyer’s cabin, much to the latter’s amusement. The lawyer would deliberately make his client sit for a long time, observing his discomfort. This was his daily dose of after-lunch fun.

He fell in love with a drop-dead gorgeous lady and married her. Though they remained childless, they shared an almost conspiratorial relationship. There were no secrets. She was quite proud that he was an accomplished flirt; joking that his adultery was restricted only to eye and hand movements. The couple simply did not fathom what was politically correct. Once, at a navjote in the Colaba agiary, he gently rubbed the bare back of a bare acquaintance; and her sailor husband barely managed not to box him. His wife would narrate this incident with great glee at parties. They, of course, enjoyed a truly blissful married life for decades.

His father had warned him that he should never go near water, as some astrologer had predicted death by drowning. That was the only advice of his father which he religiously followed. Every time a plane experienced turbulence over the sea, he became a nervous wreck. He fished out a small prayer book and fervently mouthed Yatha Ahu Vairyo. An eminent Parsi counsel sitting next to him would increase his discomfiture by telling him that the plane was experiencing a rare condition called CAT (clear air turbulence) which was highly hazardous. His breathing became shallow and he implored his fellow travellers not to joke about the situation.

An accomplished speaker, he was much sought after at legal conferences, seminars, post budget analysis meetings and even charity events. He simply loved the limelight, and when at the height of his professional career, was a popular figure. He decided to jump into Parsi politics and ended up as a trustee of an august charity. He spent most of his time mimicking the chairman and regaling his co-trustees with his barrage of jokes. The chairman was an inveterate name dropper, which enabled our friend to imitate the chairman’s nasal twang to perfection ("I met Manmohan at some function. Manmohan, you know, the Prime Minister. He enquired about my views on the state of the economy, and I said …”). Detailed analysis of any issue, bored him. He flippantly smiled, joked, ate, poked fun at all and sundry.

Gradually, he was totally out of touch with his field of practice, which was then over flooded with consultants and lawyers. Barring a couple of loyal clients, he lost most. Not that it bothered him in the slightest. He retained his joie de vivre although his increasingly stale collection of jokes and tales amused only a few. The audience at seminars now demanded hard content, incisive analysis; they did not participate to listen to insipid jokes. Uproarious laughter soon turned into sniggers. Applause was replaced with relief when he ended his talk. Increasingly, hardly any organizer invited him. Then, one day, while seated in his cabin, the roof collapsed and he suffered a severe concussion. His devoted wife nursed him to health, though he appeared disoriented, a pale shadow of his former ebullient self. He continued to attend trust meetings, though his interest was largely focussed on the sumptuous snacks. In the midst of a meeting, if food was stuck in his dentures, he would calmly remove them, and dislodge the particle with the help of a safety pin, reinstate the dentures and give a nonchalant nod.

To his credit, he never displayed any bitterness or hankered after the lost golden years. He feebly smiled at visitors and did crack a joke or two. His eyes still darted on bare backs but his hands were too weak to react. The end came rather suddenly, when a lot of water accumulated in his old lungs, and he had that drowning feeling.

Berjis M. Desai is a lawyer in private practice and a part-time writer. He considers himself an unsuccessful community activist.