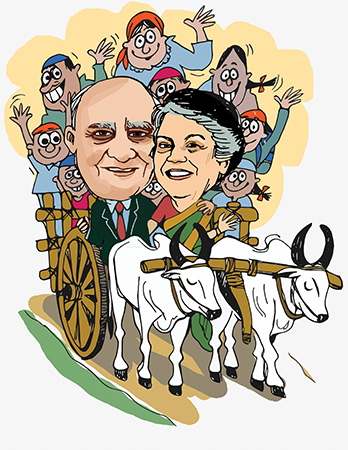

The parents

Berjis Desai

Decades ago, a Parsi colleague invited him for dinner at his home in Vansda, a village 50 km from Navsari, the town of our hero’s forefathers. The home had walls made from mud, no water or electricity, no latrine, no nothing. Dinner though comprised of aanthéli marghi (spicy marinated chicken); to provide which the family must have economized on their meals for a week. The poor are most hospitable.

"You stay in a hut!” our hero exclaimed, and then bit his tongue. He narrated the episode to his wife (for ease of reference, we shall call our hero Dinyar and his wife, Behroze). Their moist-eyed resolve to alleviate rural Parsi poverty was the beginning of a journey which would wipe a million tears and light up a zillion smiles.

Each of the villages in south Gujarat with a Parsi population was an eye-opener. The widowed mother and her 10-year-old daughter subsisting on one scrambled egg as the only meal of the day. Naked toddlers of Parsi farmers running about in the strong sun with distended bellies indicative of Vitamin D deficiency. Parsi octogenarians not able to see due to easily operable cataract. Constipated teenage girls too embarrassed to relieve themselves in the open fields. Middle aged women making half a dozen trips daily to the well to fetch water. Aching ribs due to constant coughing bouts. The aged trembling in bitter cold without a wood fire to warm their limbs. Tuberculosis. Malnutrition. Even starvation. Miscarriages. Infant mortality. Feeding mothers with dried up breasts. No hospital. No doctor. No midwife. All Parsi Zoroastrians. Shattering the myth that there are no poor Parsis.

Dinyar and Behroze, first cousins and childhood sweethearts, thought to be astrologically incompatible due to the placement of Mars in her seventh house, overcame family objections, persisted and got married. She was fond of children. They would not have any biological ones but plenty of adoring nephews and nieces, and of course, hundreds of those boys and girls in rural Gujarat who would worship them as their parents.

Illustration by Farzana Cooper

After a couple of sales and marketing jobs with two leading Parsi business houses, he started a chain of retail shops in Navsari and progressed to be a leading exporter of garments giving him an opportunity to interact with philanthropic Zoroastrian organizations all over the globe. The sponsors realized the social service potential and commitment of the couple. Money would not be a hindrance.

Huts were replaced with sturdy cottages, containing beds, chairs, tables and a cupboard. Bliss was to have a latrine of your own. Sanitation. Drainage. Electricity. Motorized pumps to draw water from the well. Borewells. Seeds to grow cash crops like sugarcane and nitrogenous fertilizers to enhance yield. Money to start a brick kiln or a mini poultry or dairy farm in the backyard. Loans to buy an auto rickshaw or a secondhand car to ferry passengers. Lessons in basic hygiene to prevent disease. Care for expectant mothers and nutrition for infants.

Making Parsi farmers self-reliant. Placing their daughters in the Avabai Petit Orphanage at Bandra to receive good schooling in the English medium. The girls blossomed into young ladies, moved up the social ladder and took care of their parents in the villages they had left behind. Special English tuitions were provided to these girls who were thrilled to eat well for the first time in their young lives.

Many a times, Dinyar and Behroze, with their growing team members, found it difficult to distinguish the Parsis from the Adivasis. They spoke the same dialect, had the same accent and habits, knew little about the Zoroastrian faith and were often dark complexioned.

Some of them had managed to land jobs as fire temple workers and pall bearers in Bombay, Navsari, Bulsar, Bharuch, Surat, Udvada and Billimora. There were not so apocryphal stories of a Mahesh transformed into a Mehernosh, given a black cap, sudreh and kusti, and employed as a chaasniwala (fire temple worker) in an agiary or as a corpse bearer in the towers of silence. Most were children of mixed marriages. Few could recite an Ashem Vohu or Yatha Ahu Vairyo. But each Parsi Zoroastrian was precious. A century ago, the saintly Dasturji Kookadaru had performed the Mazgaon navjotes, and a few decades earlier, the Gandhian social worker, Burjorji Bharucha had sponsored the Vansda navjotes, to bring into the fold children of Parsi fathers (presumably) and non-Parsi mothers.

Dinyar and Behroze worked towards assimilating these forgotten Parsis into the mainstream; to make them imbibe the Parsi culture and way of life. They saved countless families in far flung hamlets of Gujarat from being lost to their vanishing community.

"Vaishnava jan to, téné kahiyé, jé peed parayi jaane ré, par dukhé upkaar karé, toyé man abhiman na ené ré (a true Vaishnava is one who senses the pain of others and who feels no pride in relieving it),” Narsimha Mehta, the saint poet of Gujarat, sang Gandhiji’s favorite bhajan. Our hero and heroine sensed the pain of countless poor Parsis and rescued most from misery.

Help poured in. Donations from overseas Parsis. An NRI (non resident Indian) couple noticed the discomfort of traveling in a jeep on bad roads for weeks and gifted them an airconditioned SUV. Donors sponsored children up to vocational and higher education. Old age homes were constructed and now have full occupancy. Subsidized self-contained flats for the lower middle class in ‘A’ quality buildings, at cheap rent, in Navsari.

Dinyar’s reputation grew by leaps and bounds. He was elected twice as a trustee of that "most august institution” of the community. In the process, he ruffled the feathers of the orthodox. The couple were firm believers in the efficacy of after death prayers and felt that no Zoroastrian, irrespective of the method by which his body was disposed, ought to be denied the first four days’ prayers. He had witnessed firsthand the conditions in the tower of silence. He was sympathetic to the demands of the liberals for a so-called "cremate-ni-bungli” at Doongerwadi. He could not, however, convince those in authority to do so, and reluctantly, led a group which established a prayer hall for performing obsequial ceremonies for cremated Parsis. Heretic scum, they said. Enemy of the faith, he was labelled.

He found great solace in his natural constituency. People who were grateful, people who smiled despite great adversity, people who called them angels sent by the Cosmos, people who were happy with so little, people who loved and not hated.

The couple did not hit back at their critics. For there was so much unfinished work to be done rather than indulge in theological debates. After all, they were parents of so many children, young and old. The happiness they derived in seeing the poor progress and become self reliant was immense. Monitoring the activities on ground, making course correction, keeping the morale of the social workers high. It was much more gratifying than mere cheque book charity. They had discovered the purpose of their incarnation. The joy they felt when they heard the chorus of Parsi girls from rural Gujarat sing "Koi poochhé mané, kya chhé tara Zarthosht Paigambar? Dil chiri né bataoon, mara jigar ni andar (If someone asks me where my prophet is, I would say he resides within my heart),” was perhaps much more than praying five times a day. Something about hands that help being holier than the lips that pray.

Berjis M. Desai is a lawyer in private practice and a part-time writer. He considers himself an unsuccessful community activist.