Gentleman at large - I

Berjis Desai

After a spartan breakfast of toast with some thick cut lemon marmalade [purchased from Harrods during his last visit to Velaat (England)] and black coffee, he rudely ignored some question his nervous wife asked; then rather solicitously enquired about the health of his octogenarian mother; drove his recently air-conditioned Fiat out of his large but unimpressive bungalow to meet his many solicitors. Needless to add that all his solicitors, doctors, architects and accountants were Parsis. His girlfriends were not.

Jamshedji’s (we will call him that, for ease of reference), first stop was a young solicitor, he had recently engaged and become quite fond of. "Did you ever see Ilie Nastase play at Wimbledon?” Jamshedji asked. The young lawyer, harassed by work pressure on a Monday morning, politely shook his large head. "Then, you have seen nothing. Nastase had such style, such elan, so much mischief,” the older gentleman was ecstatic. The young fellow feebly smiled, not wanting to annoy an important client who simply loved to litigate. Just the other day, a notorious builder had threatened to sue Jamshedji. "Please do so, it will be my 152nd suit,” he informed the stunned builder, with a Cheshire cat grin.

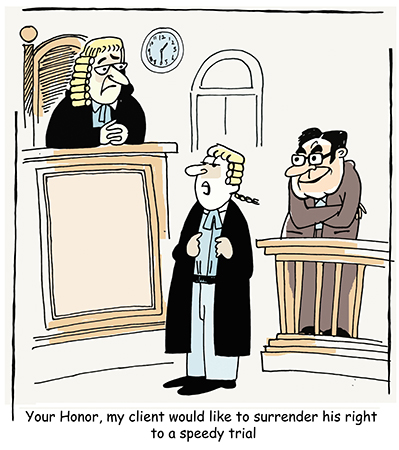

Illustration by Farzana Cooper

He insisted that the young lawyer have coffee with him at the Sea Lounge, his favorite mid morning haunt. Over much ribaldry and bawdy humor, Café Viennoise (a Sea Lounge speciality of hot coffee, cream, chocolate syrup and cinnamon) and fresh pineapple cake, he advised the young lawyer that he must never settle a litigation. A good litigation is so fascinating — getting into the witness box, being cross-examined by some dimwit lawyer and outwitting him, the suspense of the judgement. Jamshedji turned lyrical. "Keep your thumb erect, never let it bend backwards, in compromise. I hate the words consent terms,” he grimaced.

After this lecture on how litigation made him orgasmic, Jamshedji led his companion across the road to the Gateway of India. He gave a furtive glance, removed a packet from his ample trouser pocket and flung it into the sea, "That was my passport,” he whispered to the horrified young man. "After a few visits to Velaat and Switzerland, the bloody income tax fellows always ask me too many questions, about my trips.” He promptly marched to the police station to register a complaint about his lost passport. Forgetful old Parsi gentleman has again misplaced his passport.

Jamshedji then clambered up three storeys of his rickety old office building, smelling of pigeon deposits over decades, and fired his mostly Parsi staff for imaginary acts of omission and commission. Then he summoned his Man Friday — we shall call him Pestonji — for further entertainment. "Pesu, why do you insist on wearing a three-piece suit in April! You are no longer working for the bloody Brits,” exclaimed Jamshedji. Pestonji ignored the comment and said in a whining tone, "Jamshedji, we have received another draft of the Cousins’ Agreement; and it is in very bad English.” The Cousins’ Agreement was an ongoing matter, over some 15 years, about the distribution of furniture belonging to a spinster aunt, who had died without a will, leaving Jamshedji and his cousins to enjoy a robust fight. The value of the furniture was just Rs 17,000. And Jamshedji had already doled out the solicitor’s fees of over a lakh. "Pesu, how does the (expletive deleted) English matter?” Jamshedji grinned, knowing fully well the answer he wanted. "Look, Jamshedji,” said Pestonji, slightly shaking his wise head, "I am a perfectionist and even a comma in the wrong place deeply upsets me!” "What about a semi colon?” guffawed Jamshedji, who loved to irritate his old and pompous assistant. Pesu spent hours adjusting slightly tilted photo frames on the wall and arranging pin cushions, staplers and paper weights in a synchronized pattern.

Jamshedji often dropped Pesu home. Chronically constipated, Jamshedji would then deliberately break wind, imperiously refusing to let Pesu roll down the glass window [("Air-conditioning kharaab thai jasé (the air-conditioning will get spoiled)!”] to escape being suffocated by the noxious fumes. Jamshedji immensely enjoyed perfectionist Pesu’s English sensibilities being daily brutalized thus.

Being landed gentry, Jamshedji did not need to work. Though he did run a fairly successful business, trading in an unZoroastrian item, until his late 30s, when he decided it was more fun to be a full-time litigant. He fought with his cousins, his neighbors, his tenants, his co-trustees in community charities, the tax department and the government — central, state, municipal. Strangely, he was not cantankerous. Litigation simply sought him out and he did not miss a single opportunity to litigate. However, once a juicy litigation commenced, none could deprive him of the sheer pleasure of the process. He had been a client of virtually every Parsi solicitor of some merit. "In the good old days,” he ruefully recalled, "solicitors ran after me to obtain work. Now, I have to run after them to give me some time.” He deplored one particular Parsi solicitor (clever, sharp and a shyster) whom he was wary of. This solicitor represented an old Parsi spinster, who was a tenant of Jamshedji, occupying a huge flat. Our hero was apprehensive that the shyster would extract a huge price to hand over the flat, when his client died.

One evening, his favorite lawyer called Jamshedji to inform that the tenant had died, and surprisingly, the shyster solicitor was willing to hand over the flat to Jamshedji, without charging a cent. "It’s a trap,” screamed Jamshedj, "some ruse, some trickery.” However, Jamshedji was indeed handed over the flat and did not have to pay anything to the spinster’s legal heirs or to the solicitor he so despised. The young lawyer triumphantly told Jamshedji that he was a very lucky man. Jamshedji looked crestfallen and dejected. The perplexed young lawyer asked his client the reason for his low spirits.

"What is there to be happy about?” asked Jamshedji. "We have been deprived of a long, fascinating court battle with that rascal solicitor. I feel so cheated.”

If litigation was his first love, his bevy of girlfriends were not too far behind. Although not tall, he retained his handsome looks and a full shock of hair, till his late 60s. His impish gleam ensnared many a beauty. "After I am gone, I would like to be remembered as a gay Lothario, who flitted from flower to flower, sucking nectar, at every hour,” he confided to a close friend, with a wink.

To be continued

Berjis M. Desai is a lawyer in private practice and a part-time writer. He considers himself an unsuccessful community activist.