The principal

Berjis Desai

He simply loved it that generations of his students called him Hitler. World War (WW) II started in the year he matriculated and his stentorian mother began to call her only child, Adolf, a play on his first name. His carefully maintained moustache, his cultivated style of oratory at public functions (his excessive flailing of arms as he finished his speech with a half Nazi salute), and his darting eyes, reminded one instantly of the dictator. He was the first to install a public address system with the control panel fixed to his table. Those days few knew that the speaker in every room of the school was also a listening device through which he eavesdropped on conversations in the teachers’ common room. Teachers then never retired in this school, and some of them in their 70s and 80s, believed that their young boss possessed psychic powers to know what they had spoken in private. Wearing rubber soled shoes which were noiseless and his trademark half sleeved bush shirt, he emerged from the shadows to surprise a boisterous classroom or even the teachers. "Only the paranoid survive,” he said with a demonic smile.

He was not selected for the job. As the only nephew of his bachelor uncles who were co-principals, he walked into the principal’s cabin. Of course, in all fairness, he would have perhaps landed the job, even on merits; albeit a few years later. He was an ideal, though not brilliant, student of the school for 11 years, during which he impressed his uncles with his perseverance and dogged determination, expressed through his unusually small and mean handwriting. Within a decade, he managed to usurp power from his kind and genial uncles, sons of an eminent educationist who had founded this school during Queen Victoria’s reign. One of the uncles lost his mind rather early and would loudly recite passages from Shakespeare’s plays, much to the amusement of students gathered outside his cabin. The other fell hopelessly in love with a Parsi teacher who warmly reciprocated, but Hitler managed to browbeat the couple into shelving their advanced plans of matrimony on the grounds that a workplace romance by a senior principal with a teacher may affect the moral fiber of the students.

Illustration by Farzana Cooper

Having consolidated his position thus, he married a matronly school teacher from Navsari, who complemented his policing skills. She soon became the assistant principal, and the couple reduced the old uncles to just sitting on the stage at the annual prize distribution function and benignly smile at the students. Alongside would sit the principal’s parents, a small time solicitor and a grumpy lady. Listening in rapt attention to the stirring speech of their son whose invariable punchline was: "The best is yet to come;” borrowed, of course, from the Fuhrer. Power hungry and autocratic as they were, the couple was impeccably honest. The school received no government grant, as he would brook no interference from lowly education inspectors. Soon it was converted to a public charity and run efficiently. The principal lived a frugal life, staying in a dilapidated old building of five-storeys which had no elevator (due to WW II restrictions) and travelled in a tiny baby Hindustan car which he drove with great concentration. He created a makeshift cabin for his spouse in a corner of the third floor balcony which outwardly appeared to be in imminent danger of collapsing. They enjoyed the peculiar camaraderie of the childless.

He taught English to the 11th grade and was a decent and competent teacher. The school taught in both English and Gujarati mediums; teachers, therefore, often forgot which medium of instruction a class was following, and mostly lapsed into Gujarati, much to the chagrin of a handful of students who did not understand Gujarati. The principal’s wife employed her childhood friend, a midget art teacher who would pick on a student by suddenly shouting, "tamé (you).” She once screamed "tamé” at a hapless Tamil student called Murudeshwar who was punished for not responding. When his parents protested, they were told by an octogenarian Parsi math teacher that after all this was a school for Parsis, Gujaratis and Bohris. This greatly upset the principal, who unlike his hero, did not believe in a superior race.

The principal loved people in uniform and was the first to introduce Road Safety Patrol (RSP) in his school. He was elected as the chief RSP commissioner and donned the khaki uniform and cap, with all regalia and medals, on ceremonial occasions. This satiated his intense craving to look like his object of adoration. He was invited to join a then coveted social service club’s main branch, which then comprised of the princes of business and eminent professionals. They, however, gave him no inferiority complex and he held his own; and rose to ultimately become its president. He and his lady wife became quite popular with the elitist club members, whom they entertained at their modest home. The principal refused to chain his aggressive Indian pariah dog sniffing at nervous guest ankles, perhaps so that they would eat less. He would proudly display his knuckles where the dog had bitten him.

The principal’s wife was a strict disciplinarian and soon came to be dreaded by teachers and students alike. Her cherubic pout earned her the nickname, "Rasgulli (a popular Bengali sweet).” Two rowdy brothers from the Anjuman-e-Islam School were admitted into this staid institution. They hid behind pillars and shouted "Rasgulli,” much to the horror of the principal, who managed to catch the younger brother and wallop him. This incensed the elder fellow to dump four kilos of sugar in the carburettor of the baby Hindustan, compelling the couple to travel by taxi for a couple of months, after which they posted a young school peon to guard the car, by standing next to it from 10 to six. The principal was quick to expel students, including the son of a powerful trustee of the school trust, for any gross act of indiscipline. "Never take prisoners,” he smiled. "I am always fair and equal in meting out punishments,” he said.

One day, during school, a rumor spread that his missus had fallen from the balcony. All naturally rushed to that famously tilting balcony on the third floor, thinking her cabin (along with her) had smashed to the ground. Soon they learnt that it was not his wife but his mother, who, after some minor domestic altercation, had consumed kerosene, and then, out of abundant caution, jumped out of the fifth floor rear window of their residence, to instant death. The principal was an oasis of calm during the funeral. You had the right to take your own life, he believed. After all, hadn’t his hero put a gun on his head, to prevent falling in enemy hands? Strangely, this incident further strengthened the bond between the couple.

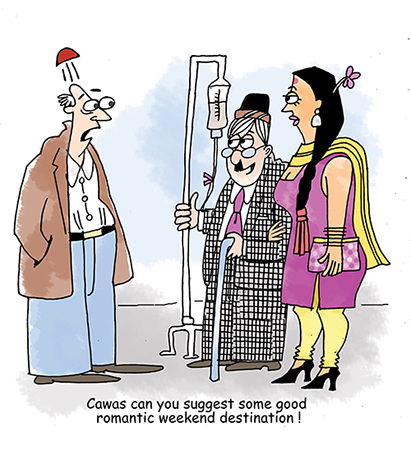

After a short illness, his wife suddenly died in her late 60s. The forlorn principal began to spend his evenings listening to music by the German composer Richard Wagner. The trustees nudged him to retire but allowed him to continue as director of education. Soon after his enforced retirement, he too fell seriously ill but cheated death. It was then that a clerk from the school, a stoutish Telugu lady, nursed him to health. Murmurs about a workplace romance between the senior principal and a clerk 25 years his junior reached the trustees including the one still smarting under the humiliation of having had her son expelled by the principal. "Desist,” they said. "It is after all my family school,” he remonstrated. "Not any longer,” reminded the irate charity trustees. Attack Poland. "What if she was my wife?” he asked. "You wouldn’t marry her, would you?” they asked incredulously. Gobble Czechoslovakia. A fortnight later, the trustees received his wedding invite. Bomb Britain. The marriage was celebrated with gusto including a honeymoon at 72. Invade Russia. He proudly flaunted his new, young wife at his club functions, making the squeamish members squirm in discomfort with someone who was so obviously underclass. He couldn’t care less. He was proud of her and wore it on his sleeve. The regular flow of adrenaline revived him and he enjoyed matrimonial bliss till his death at 86.

Berjis M. Desai is a lawyer in private practice and a part-time writer. He considers himself an unsuccessful community activist.