Is Gujarati no longer our mother tongue?

Berjis Desai

If you were a

non Gujarati speaking student at the venerable Bharda New High School in the 1960s, there was a reasonable probability that you were unable to follow what was happening, at least during a quarter of the time. Retirement age was an alien concept and Parsi teachers in their sixties and seventies lapsed into Gujarati every second sentence. Trying to explain an equation, x=y=z, a math teacher called

Mr Khori used to say, "

Maathoo

dholiya ni

aai

bajoo

muko, ké péli

bajoo

muko,

gaan to

vacchej

aavani (whether you put your head on one side of the bed or the other, the ass will remain in the middle).” Gujarati and Bohri pupils could comprehend the proceedings, save some

hard core Parsi Gujarati. Scant regard was paid to the English medium of instruction, as most teachers, who also taught in the Gujarati medium, would often forget which class they were addressing. The stray Maharashtrian or Sikh or South Indian child could have as well been in a school on Mars. Almost all Parsi pupils belonged to the lower and middle classes and Gujarati alone was spoken at home. Parsi Gujarati, of course, was adored by the Gujaratis and

Bohris as sweet sounding. The same story it was, with all Parsi managed and owned schools like Sir Jamsetjee Jejeebhoy and Byramjee Jeejeebhoy and Master Tutorial; and to a somewhat lesser extent with Bai Gamadia and Bai Bengalee.

Barring the initial migrants into Bombay — Petits, Jeejibhoys, Wadias and Camas — the nucleus of the fast Anglicized Parsi aristocracy, most later migrants from Gujarat thought, fought, swore, exclaimed in fear after a nightmare, all in Gujarati. You do all this only in your mother tongue. Many of these first generation migrants were schooled in Gujarati and fluently wrote, or at least read, the language. Jamé (then a daily) and Mumbai Samachar were read by most Parsis. An English prayer book in an

agiary was a rarity, as almost all could read Gujarati. Even the rich Anglophiles were comfortable conversing in Gujarati. Most

mobeds barely understood a few English words and

behdins instructed them in Gujarati. The original side of the Bar at the Bombay High Court was dominated by Parsis and Gujaratis; and too bad if you did not follow the language. The political correctness of apologizing for an accidental lapse into Gujarati had not then arrived. Same was the story with the Bombay Stock Exchange and the then thriving Parsee General and Masina hospitals and the consulting rooms of eminent Parsi doctors. Most Parsis spoke atrocious Hindi with a

much lampooned accent, except the late Parvez Katrak who enthralled Hindi speaking audiences with his mellifluous rendition of Kabir’s

dohas. But nearly all Parsis then spoke decent Gujarati, and most managed to praise the

ganga’s (domestic help’s) good work in faltering Marathi.

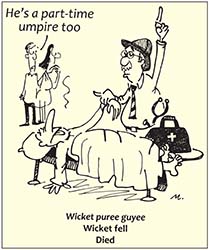

Illustration by Hemant Morparia reprinted with permission from Parsi Bol

A

micro minority spoke what was somewhat derisively termed as

shuddha (pure) Gujarati. Strangely, these

shuddha speakers would seamlessly switch over to the Parsi dialect, depending upon the listeners and the occasion. Our father, as editor of The Bombay Samachar, would converse with his colleagues in pristine Gujarati, and joke with his brother-in-law at home in Parsi Gujarati. We ourselves acquired this ability without any effort. The Jamé and Kaiser used Gujarati which was a mix of the pure and the Parsi version. Novelettes, serialized by both these newspapers were written by Parsi amateurs (

Piroj Mau and Aloo Rusi

Dodhi were quite prolific) in a confused style, avoiding bombastic Gujarati words which would have been beyond the comprehension of the lay Parsi reader.

About four decades ago, the decline of Parsi Gujarati began in Bombay. Marathi replaced Gujarati as the second language in schools. Parents conversed increasingly in English with their children. The Jamé ceased to be a Gujarati daily and turned into an English weekly. The Kaiser-e-Hind, like its namesake, disappeared. Khordeh Avesta copies in English proliferated. Parsis began to think, fight and exclaim after a nightmare, in English; the only exception was that Parsis continued to swear in Gujarati, at the dogged insistence of the Dadar Parsi Colony ("Where is that f_____newspaper?” simply does not sound the same as "Where is that madar____ newspaper?”). In the High Court, now hardly anyone lapses into the native tongue. Mobeds receive service orders for

afringaan,

farokhshi and

baaj online in English. The modern

practising

mobed is comfortable, if not fluent, in English. Just the other day, we heard a pallbearer at the Doongerwadi grumble to another, "The body was too heavy, boss.” Unlike the olden days, nurses and junior doctors at the Parsee General give a blank look if the attendant of the patient says that "évan né

chhati ma

bahuj dookhéch (he has severe chest pain).” The editors of this article insist that we translate every Gujarati phrase used in this column.

As for the Bharda New High School, not a single teacher and not a single of its 1,500 students is a Parsi. Su

dahra

aayach (and we won’t translate this one)!

Berjis M. Desai,

senior partner of J. Sagar Associates, advocates and solicitors, is a writer and community activist.