A story of two funerals

Berjis Desai

After considerable thinking, it was decided to consign my 93-year-old mother’s body to the Towers of Silence. From the same bungli, where my 55-year-old father’s body began its last journey some 42 years ago, the priests of the oldest Bombay agiary, Banaji Limji, recited the geh sarna prayers for my mother, a few weeks ago. Some traditionalist groups sent me congratulatory messages for what they exultantly termed as my "correct decision.” Several reform minded friends remained silent but wondered as to why she had not been cremated, despite the availability of the Prayer Hall at the Worli crematorium.

Fifty years ago, in his weekly column, "Parsi Tari Aarsi,” in the Bombay Samachar, which he also edited, my father provided ample space to the diminishing number of vultures. Community activist Dara Cama had circulated photographs showing undisposed bodies with partially recognizable faces. Dr Aspi Golwalla, chairman of the Bombay Parsi Punchayet (BPP) and an eminent physician, had entered the dakhmas, along with another trustee and a leading lawyer, Shiavax Vakil, to assess the true state of affairs. All three, Cama, Golwalla and Vakil, were abused, threatened and vilified. Golwalla was the personal physician to the Camas of Bombay Samachar, while Vakil was my father’s close friend. They corroborated Dara Cama’s horrific album. Dervish Irani, the legendary caretaker of the Towers confirmed that the situation was worsening by the day. Eight years later, my father, diagnosed with terminal cancer, had sufficient time to contemplate the possibility of cremation. He was a peculiar blend of a devout, daily praying Zoroastrian, an ordained priest, yet a devotee of Shirdi Saibaba and a witness to many interfaith marriages, which required courage those days. In his final hours, he said that he preferred to exit the way his forefathers had.

All the traditional prayers were performed in the Hodiwala Bungli starting with the bhoi pur nu bhantar [prayers recited by a mobed seated before a ruvaan (corpse), from the sachkar (ritual bath) to the beginning of the gah sarna] which began at dusk till the early hours of next morning. Throughout the night the experienced mobed’s mellifluous tone, rising and falling in a crescendo, over the flickering sandalwood fire fed with frankincense in the dim lighting of the bungli, helped his dearest to come to terms with their grief. The body, wrapped in white and placed in a rectangular space, a zone of protection created by many elaborate occult rites, lay in state, relieved of its earthly pains; a solitary divo (oil lamp) flickering near the head. The almost total silence according dignity to death. Then in the morning, the memory erasing gah sarna prayers, from the Ahunavad Gatha, sung in an amazing synchronicity, by a pair of mobeds used to each other’s rhythm, ending with the emphatically pronounced Avestan power mantra, Nemascha ya Armaitish izha-cha, thrice. The resulting silence broken by the shuffling of feet of the mourners bowing before the body, one by one. Moist eyes, stifled sobs, the realization of the fleeting nature of human existence, all mingled together, as the procession went past the many non-Parsis lining the road on either side.

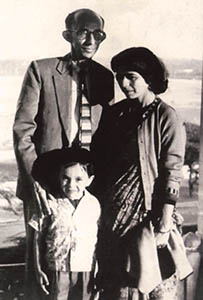

A young Berjis Desai with his parents Minoo and Mani

Uphill, the iron mesh stretcher was placed on the marble platform, the face exposed to the encircling mourners for the last time. They later, awaited the cue of the nassessalar clapping thrice to signal that the body had been placed in the well to begin praying Namaskar dakhma no from a tiny book. Some peacocks wailing their distant protest at the clapping. The ritual of dipping your finger in the consecrated urine of an albino bull (some seasoned mourners deftly avoiding the urine dispenser), the kusti and then bowing before the Sagdi fire. I saw plenty of vultures when his body was consigned.

Those days, the death certificate was issued by the BPP itself from its office near the Sagdi. I collected the crisp, green certificate certifying my father’s consignment to the dakhma; a strange feeling of catharsis at the death of the person you loved most, as I made my way downhill to be consoled by those not permitted to join the funeral. Two nights later, the uthamna before dawn before that empty rectangular space and the still flickering divo. The Dog Star Sirius (Tir Yazad) above the bungli, brightly shining in the summer sky as the manthric vibrations of high energy resonated within. The family made their way up to the Sagdi fire where the priest recited a powerful intonation to the soul which had just crossed the bridge of judgement by striking the bell 12 times and uttering the name of the departed. However traumatic or young death may have been, most went home with an overwhelming sense of peace.

In the intervening four decades, many a crusader, including this columnist, passionately wrote about the failure of dakhmenashini. None more effectively than the fearless Dhun Baria whose videotapes were shown on national television. A former qawwali singer under the stage name Mahajabeen, the feisty Baria shook the establishment as never before. Her response to midnight callers threatening death was so original that they soon realized that Baria was from a different planet. With nonsensical plans of the BPP to breed vultures in captivity failing spectacularly, the solar panels operating at high intensity dehydrated the body in three to five days with wisps of smoke emitting, except during heavy rains. Ozone dispensers were deployed to mask the occasional stench. Bones and undisposed remains gathered and buried more frequently than before. Baria and I nearly wangled a cremate ni bungli at Doongerwadi. Dinshaw Tamboly succeeded in establishing the Prayer Hall for Parsi crematees.

My mother and I debated at length the disposal method she wanted for herself. Public crematorium is not clean, she observed after attending her brother’s and nephew’s cremations. Can we not have a crematorium for Parsis only? she asked. Like her husband, a daily praying Zoroastrian and a fervent believer in the efficacy of after death prayers, she was not too impressed with the new Prayer Hall. Does not have the same ambience and atmosphere, she twitched her nose. Her ambivalent approach continued until her last days, being super alert mentally. Do what you think fit, she smiled. Just before dawn, as she peacefully breathed her last, with her head cradled in my arms, I dialled a surprised Hoshedar Panthaki of Banaji Agiary to arrange for the prayers and then called for the Doongerwadi hearse.

I wanted her to be protected by the consecrated circuits of the dakhma connected with the fire temples through lines in the earth. I wanted her to have the same prayers and rites performed as she had done for so many of her loved ones. If this sounds like mumbo jumbo, so be it. My father was right. There is nothing more beautiful than exiting in the same manner as your forefathers did. Perhaps in the not too distant future, there will be an electric crematorium in the dakhma to ensure spiritual protection and expeditious disposal at the same time. Almost certainly, a few years later, non-Parsis will be permitted inside the bungli. The Towers will continue to dispel grief and soothe broken hearts.

My mother’s funeral and other ceremonies were an identical rerun of my father’s funeral more than four decades ago. Her favorite priests, whom she patronized throughout her long life, prayed for her with passion. After the pre dawn uthamna, the Sagdi bell was struck 12 times and Sirius shone above the Hodiwalla Bungli, exactly as before.

Berjis M. Desai is a lawyer in private practice and a part-time writer. He considers himself an unsuccessful community activist.