A matter of faith

Berjis Desai

Although he had just stepped out of the shower, he washed his arms and face, drank a glass of water to cleanse his mouth, turned eastward, picked up his kusti, and recited the Kem na Mazda in a sonorous voice. During Ahuramazda Khoday, he vigorously snapped the kusti, tied the perfect reef knot of the Boy Scouts, placed the forefinger of both his hands in the knot and recited the Jasame Avangahe Mazda. Since he rose at dawn, this was his fourth kusti; one of the 20 odd which he would complete before retiring to bed. His faithful red velvet cap firmly worn except for the uncomfortable four minutes under the shower. He sat down and had recited his farajiyat ( mandatory) prayers for about 40 minutes, when he saw that the toe of the maid on her haunches sweeping the floor touched the gramophone whose long wire was in contact with the base of the chair he was sitting on. He gently admonished her and began the ritual afresh; the juddin contact having broken the protective circuit of his barjisi jiram.

He was not at all upset at the prospect of reaching office late as a result of this little mishap. Anyway, he reached the office of the ancient law firm of which he was an equity partner, only around three p.m., having completed his visits to every fire temple in Bombay whose salgirah fell on the day. He poured milk into a bowl of Quaker oats, cut one overripe banana, recited the baaj before eating (baaj jamvaani), ate with his eyes adoringly gazing at the huge portrait of the Prophet on the wall; wore his unchanging white cotton shirt and slightly tattered black jacket (he possessed three ties during his legal career of 50 years), recited the baaj before entering the washroom (baaj haajat java pehlaani) , one more kusti, of course, and sprightly went down the staircase, exchanged pleasantries with some unemployed haandaas (loafers) whiling away their time before lunch, near the office of the Baug; sat in his baby Hindustan car, and was about to whisk away, when Amy walked up to the car and asked for a lift. "Of course,” he said lovingly to the girl, who, like most women in the colony adored this saintly gentleman. As she sat next to him, a cold sense of horror descended upon him. What if. He had to ask the awkward question. "Amy dear,” he said in a soft tone, "I hope you are not undergoing your monthly discomfort?” With great difficulty, Amy suppressed her laughter and replied, "Uncle, unfortunately, I am.” This was clearly not his day. He tendered a thousand apologies to the girl whom he asked to get down from his car. He parked it, clambered up the two stories, had another bath and kusti, instructed his office peon to wash the car seat, and hailed a taxi. It was nearly noon and he still had to visit and pray for an hour each at two agiaries. A late vegetarian lunch, after of course, the baaj jamvaani.

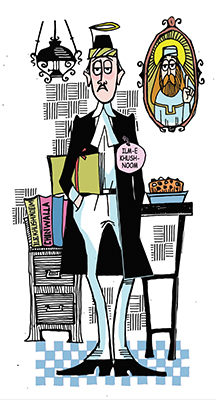

Illustration by Farzana Cooper

When he reached office at four, a bunch of agitated Parsis were waiting at the reception. The CER [Committee for Electoral Rights who won the 1981 Bombay Parsi Punchayet (BPP) Anjuman Committee elections], they said, had won every seat in the Anjuman Committee except one. The BPP had slipped into the hands of heretic reformist scum. We must file a suit and obtain a stay order against the declaration of results, they whined. There are no legal grounds, he calmly advised, but nevertheless I shall prepare the suit. Free of cost, naturally. He never took fees from any Parsi charity or community issue, even if he spent months over it. His sharp legal mind did not take long to prepare the suit papers. He went to bed at midnight after reciting prayers for an hour. The next morning in court, dozens of boisterous Parsis from both sides, greeted him. His opponent solicitor, also a Parsi, warmly shook hands with him. "I feel like killing you for wasting time with this frivolous suit,” he said, "but then you are such a sweetheart.” The suit was dismissed in 10 minutes. "Sorry,” he told his opponent, "but I had to discharge my duty.”

Discharge his duty, he selflessly did. Towards his parents, his teachers, his family, his community and his faith. He had become a vegetarian, a teetotaller and a lifelong celibate, after imbibing the teachings of Ustaad Saheb Behramsha Shroff, a Zoroastrian mystic, who founded Ilm-e-Khshnoom (path of knowledge) based on occult Zoroastrianism. Akin to the Theosophy of Madame Blavatsky and Annie Besant, Khshnoom believes in karma, reincarnation, vegetarianism and the potent effect of our Manthric prayers to be recited after following tarikat (pristine ritualistic purity of body and mind). The Great White Brotherhood is in the form of the Aabed Sahibs of Demavand Koh in Iran, who had granted young Behramsha an audience.

Had he devoted time to the practice of law, the brilliant solicitor would have carved a niche for himself. However, he experienced the greatest happiness in praying solo early afternoon before the holy fire in a deserted agiary; anonymously donating to his needy brethren; reading tomes on Ilm-e-Khshnoom; providing free legal services to Parsi causes. Tall and handsome, he radiated compassion and that glow which adorns those in whom no desire for bodily gratification even emanates. He was a fundamentalist alright but never spewed any indignation at those who thought he was a fruitcake or on the lunatic fringe. His steadfast belief in doctrinal purity meant that he disapproved of interfaith marriages, conversion and adoption of those not born of both Parsi parents; even blood donation and organ transplants. This, however, did not prevent him from loving and caring for all beings. In his colony, and in courts, in his law firm too, his excessive religious fervor made him an eccentric and someone to be mocked at during a dinner conversation. People, after all, feel uncomfortable with those who are different.

Berjis M. Desai is a lawyer in private practice and a part-time writer. He considers himself an unsuccessful community activist.