Foul mouthed parrots and a privileged hen

Berjis Desai

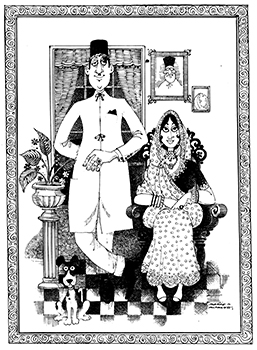

Amongst all Indian communities, Parsis are the loneliest. Bachelors, spinsters, widows and widowers and the childless are to be found in a staggering number of households. Considering their yearning for companionship and severe emotional deprivation, it is surprising that so few Parsis keep pets. While the community boasts of many dog and horse lovers, some of its members are also fond of the odd and the exotic.

Our earliest memory of this incarnation is being rocked on the protruding belly of a genial bearded dasturji lying on a four poster bed with laced mosquito nets. He was our grand uncle in Navsari who had returned from Aden after officiating as a priest in the local agiary and had brought along with him a handsome grey and white African parrot of the cockatoo family (kakatavvo, in Parsi dialect). This particular bird had an amazing ability to mimic the human voice, coupled with a terrible sense of timing. He learnt the choicest Parsi abuse from the lads roaming around the moholla (locality) and would daily shower the same on a prudish neighbor returning from the atash behram across the street, spoiling his pious state of mind. Later, when our widowed grand-aunt was the lone survivor in a three-storey house where once a family of 100 members resided, Kaskoo, as the parrot was called, would be heard, in the middle of the night, advising her to go to bed.

Many Parsi homes in Gujarat had as pets the less exotic cousin of the kaskoo, the green parrot with the curved red bill, in a circular cage hanging in the patio, whose vocabulary was limited to a couple of words like "popat mithu (sweet parrot),” but who had the privilege of being the first in the household to be served a vegetarian meal. Our maternal grandfather, a noted caterer who conjured up a mean liver curry, kept a succession of these green parrots and was proud to be known as Behramji Popat. Bombay Parsis, in the yesteryears, were fond of keeping love birds, natives of Madagascar, small and affectionate, who made more noise than love. Our uncle, a professional magician maintained a flock of white pigeons; they smelled awful, would voluntarily return home every evening to captivity and did not seem to mind being squeezed into various parts of the anatomy of our uncle’s buxom assistants, only to triumphantly appear on stage with an excited flutter.

Many Parsi homes in Gujarat had as pets the less exotic cousin of the kaskoo, the green parrot with the curved red bill, in a circular cage hanging in the patio, whose vocabulary was limited to a couple of words like "popat mithu (sweet parrot),” but who had the privilege of being the first in the household to be served a vegetarian meal. Our maternal grandfather, a noted caterer who conjured up a mean liver curry, kept a succession of these green parrots and was proud to be known as Behramji Popat. Bombay Parsis, in the yesteryears, were fond of keeping love birds, natives of Madagascar, small and affectionate, who made more noise than love. Our uncle, a professional magician maintained a flock of white pigeons; they smelled awful, would voluntarily return home every evening to captivity and did not seem to mind being squeezed into various parts of the anatomy of our uncle’s buxom assistants, only to triumphantly appear on stage with an excited flutter.

In the sultry summer of 1832, the English decided to cull stray dogs, notwithstanding the entreaties of enraged Parsis including a delegation led by none other than Sir Jamsetjee Jejeebhoy. On June 6, the Parsis rioted in the streets of Bombay to express their boiling anger at the treatment meted out to their canine friends. These are chronicled as the Mad Dog Riots. In the years following, Parsis rioted against Muslims too, over some religious issues, with far graver consequences. The Vendidad classifies the dog as a divine animal gifted with special sight to detect any sign of suspended animation; hence the dog being brought to eye a corpse at funerals to prevent any Parsi being consigned before his time. The dog is also supposed to destroy the impurities emanating from dead matter or naso, surrounding a corpse.

We knew of a Parsi family taking affront if their dog’s name was not mentioned in the lagan ni chithhi (wedding invite) and would refuse to attend the function. On the other hand, the Bombay Parsi Punchayet (BPP) forbids its tenants from keeping dogs in the premises, under their leave and license agreement; though we have not yet heard of an eviction suit being filed on this ground by the otherwise trigger happy trustees. We also know of a senior counsel in the High Court, much sought after for his scintillating brilliance and court craft, who summarily terminated a critical meeting with a corporate bigwig and returned a lucrative brief, as his nervous client accidentally kicked the counsel’s Pomeranian who was sniffing at his ankles.

Parsis, usually, though not always, of aristocratic lineage, were pioneers in founding and managing animal hospitals, stray dog shelters, the Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals and dog shows. Muncherji Cama, the chairman and managing director of The Bombay Samachar would brave ill health and fly to Tashkent and far flung countries near the Caspian Sea to judge dog shows. After appreciating disciplined dogs for decades, he resigned in disgust from the BPP trusteeship. The reverence and love which Jains and devout Hindus bestow on cows is showered by Parsis on dogs.

Few Parsis like purring felines though. Years ago, in search of paying guest accommodation, we came across an old Parsi spinster staying alone in a seven-room house at Dhobi Talao, reeking of eucalyptus oil, countless empty bottles of the liquid lying strewn all over the floor; and to complete the bizarre tableau, more than a dozen cats perched on window sills and the furniture, eyeing the nervous jugular of the visitors, who, of course, beat a hasty retreat.

While tortoises and fish are fairly common, some display more exotic tastes. A couple called Nagrani Nargis and Yogiraj Jimmy, leaders of a cult which once upon a time had a sizeable following amongst Parsis and still has amongst non-Parsis, reportedly kept colorful snakes at home, including a defanged cobra. On naag panchami day, the snake couple were said to visit the dakhmas with their Parsi followers to perform some strange rites, until some enraged orthodox Parsis reportedly manhandled the rather frail Yogiraj who beat a hasty retreat.

During the days of the Raj, in Bareily Cantonment, a Parsi who ran a popular shop selling liquor, ham and cheese to the British soldiers, kept with him at the till a fully clothed chimpanzee who greeted the customers with an eerie smile and followed his master home where he would dutifully untie the owner’s shoelaces and carefully place his shoes in the closet.

In Gujarat towns and villages, Parsis reared poultry for eggs and meat. However, each home would have a pet hen or two, who would live to a ripe old age instead of suffering the usual fate of their less fortunate kind, that of ending up on a plate alongside potato chunks. The pet hen was easily identifiable by a colorful chain round its neck and would strut around pompously, having instinctively understood its special status. The rooster, on the other hand, regarded by Parsis as the angel of dawn, was sacrosanct and never consumed. He dominated his harem with gusto and kept the eggs and chicks coming. On Dassera, a red kanku (vermilion) tilo would be applied to its forehead and he was garlanded with marigolds.

Of course, the ultimate exotic pets were the ones aspired to by the then trustees of the BPP, who made extensive plans to breed vultures in captivity and wanted well-off Parsis to sponsor a vulture baby. One paid for its feed and upkeep, including medicines. The BPP said it would forward a quarterly progress report with a photograph of one’s adopted pet (‘Silla’s baby is cuter and more cherubic than Pilloo’s, isn’t it?’). Unfortunately, there were no takers.

Berjis M. Desai, senior partner of J. Sagar Associates, advocates and solicitors, is a writer and community activist.