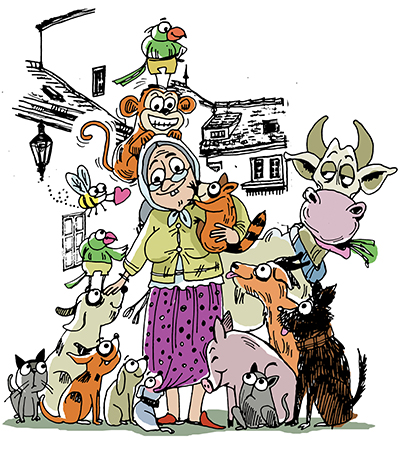

Animal farm

Berjis Desai

Every night, Burjorji’s routine remained unchanged. After dusk, he washed his hands and face; recited Sarosh Baaj, Aivesruthrem Gah, Atash Nyaish, Vanant Yasht, Doa Tandarosti; injected insulin in his stomach and sat down at the dining table. Shirinbai, his wife of 53 years, alerted by his clapping during Vanant Yasht, knew that the prayers were about to be concluded and started to warm the tapéli (utensil) containing their spartan dinner. They ate in silence. She retired to the kitchen and he wound the gramophone, inserted a new needle in the hand bar, and played a black vinyl record. As Gohar Jaan sang a thumri (light romantic Hindustani classical music), he walked up and down to aid his digestion, locked the front door and the windows, and slowly clambered up the wooden stairs to his bedroom on the first floor of his house. A giant four-poster bed with a machhardaani (mosquito net) awaited him. He gingerly walked onto the balcony and carefully checked whether the topli (woven grass basket) had enough not-so-small stones. Then he did the last kusti of the day and placed his bald head on the pillow. It was only 9 p.m. but silence reigned already in Seervai Vad. Within minutes, he began to snore.

As the many grandfather clocks in the Vad chimed 12 unsynchronously, the pi-dogs started to yelp, bark, cry and howl. Burjorji woke up with a start, rushed to the balcony, picked up a stone from the topli and aimed at a dog standing quietly. It struck bullseye and the animal scampered away in pain. Another came running but the stone missed him. He accused the dog of having incestuous relationship with his mother. This stone throwing exercise was repeated during the night, every time the dogs created a ruckus.

Illustration by Farzana Cooper

Next morning, Goolbai, the neighbor across the street from Burjorji, offered left-overs to the injured dog, grabbed him and applied tincture of iodine on his wound. The dog allowed Goolbai to tend him with a loving expression in his eyes. Ever since she was a little girl, Goolbai knew each mohalla dog by his or her name. If a bitch died after delivery, she adopted the litter and fed them milk by dipping a torn sudreh into the pan and squeezing out drops. She had no hesitation in cleaning and medicating dogs with severe skin infection. "Kohi gayela kootra né haath lagarta, tumné soog nathi laagti (Don’t you feel revulsion handling mangy dogs)?” Shirinbai, twitching her nose, would ask. Goolbai would simply smile. She was more morose when a mongrel breathed his last, rather than at Muncherji Mongrelia’s funeral.

During his daily walk to the Atash Behram, when Burjorji saw a particular dog which had disturbed him the night before, he would shove his curved handle wooden stick into the offender. He was an inveterate canine hater. However, he adored monkeys. Navsari had grey langurs and red bottomed rhesus monkeys [called lal gaanwalo vandro (LGV)], the latter being more aggressive. On one occasion Shirinbai was surprised by a LGV standing before the full length mirror affixed to the large rosewood cupboard and preening. He ignored the lady but scooted upon seeing Burjorji. During his stint as a salesman in Bareilly, Burjorji had a pet pygmy chimpanzee who could tie and untie his master’s shoelaces and grin mindlessly at the Parsi who, thereafter, developed a lifelong fascination for simians.

While little children tied colorful ribbons around the necks of young goats who bleated if they were thirsty and scratched their backs by walking against a wall, people were wary of the nasty looking and foul smelling bakro (he goat) with sharp horns and sporting a beard. When a young goat went missing, children were told that it had migrated to another mohalla; of course, the truth was that it had ended up being that tender kid gos in white gravy on a lagan nu patru.

The ruling Gaekwads had donated a couple of old elephants to the local temple in Navsari. These pachyderms rolled into the narrow mohallas during Dusshera or other festivals. Parsis offered coconuts and other goodies to these animals which were considered auspicious. Adivasis routinely brought tame bears and sold amulets to be worn around the neck after the animal had licked them. Parsis bought these amulets surreptitiously, as it was an unZoroastrian extra-religious practice to wear these dhootam dhaatum madaliyas (hocus pocus medallions) underneath the sudreh.

Beggar ladies brought an emaciated looking cow once a week and many Parsi ladies fed it grass, touched the cow and then their eyes. Conjunctivitis was unknown then. The Prophet had expounded cows to be holy and therefore Navsari Parsis never ate beef. Though pigs had not been similarly endorsed, Parsis abjured pork too. Strangely, in the more snooty Parsi mohallas seldom were pigs seen, although they roamed all over juddin (non-Parsi) Navsari.

Cats were almost universally despised; particularly black ones. The mohalla often sponsored an Adivasi to bundle black cats in a gunny bag, lest they ran across and brought bad luck. Green parrots in a cage on the portico were ubiquitous in Navsari homes and some parrot lovers were known by the surname Popat instead of their family name; like a famed caterer called Behramji "Popat.” Decades ago, there was a mythical Parsi called Peshotan Popat who wrote scathing articles in the Parsi Press and gave sleepless nights to the then trustees of the Bombay Parsi Punchayet. Where he flew away, no one knows.

Berjis Desai, author of Oh! Those Parsis and The Bawaji, occasionally practices law.