On noses, twitches gaits and traits

Berjis Desai

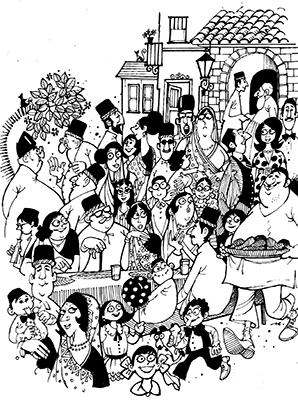

Considering how handsome our Iranian ancestors were, and how exquisitely featured the Indian women who surely intermarried in large numbers, the resulting product is rather disappointing. The Persian features were vulgarized perhaps by the practice of marrying our first cousins, mostly paternal. You can yet spot a Parsi from a mile.

Although the pink glow of Iranian cheeks is rare, the complexion survives almost unscathed despite the harsh Indian sun. Its shades are becoming darker however. From the near Caucasian (some aristocratic Parsis may be very fair due to marrying Anglo-Saxon and European ladies!) to the somewhat derisively referred to as the doodh paoo variety (white bread soaked in milk); to the Oriental yellow pale anemic look; to the Mediterranean dusky; and the rare, dark Parsi.

Physiognomy, the study of correlating physical features with psychological characteristics, may be assailed as a pseudoscience; however, there is something to be said about the link between Parsi noses and Parsi peculiarities. Most of us have a longer one than other Indians, which sharpens our olfactory senses. Many of those who inhabit the lunatic fringe believe that a Parsi, provided he is born of both Parsi parents, has no body odor; and the long nose ensures that you are repulsed from having any bodily interaction with non Parsis.

The typical Parsi nose is often hooked like a beak and classified in physiognomy as a Roman nose. Anecdotally speaking, the blue-blooded families often have long proboscis, and the clan is proud of it. One gentleman from one of these ‘proud of nose’ families, in his seventies, fell hopelessly in love with a lady a quarter century younger who was upset by the thick clutch of grey hair peeping out of her prospective beau’s nose and gifted him a conical shaped battery operated nasal hair remover (strangely available only in Singapore chemist shops). The elated man thrust the object in his nostril and pressed the switch. Designed for gently nipping a protruding hair or two, the device got terribly entangled in the thicket with excruciatingly painful consequences. He ran screaming with the device still whirring inside his nose, until his clever cook deftly removed the battery and ended the torture. He took it as a cosmic sign to remain a bachelor.

The Parsi ear is a close rival to the Parsi nose in its distinctiveness. Few Parsis have small ears. Thick and large ears is the norm, which indicates vitality and courage, according to Chinese face readers. Rarely, you get different sized or shaped ears; such a person experiences many crisis in early years and much success in the later part of life. Parsis often have protruding or sticking out ears, called bakkra na kaan (goat ears). Elderly Parsi gentleman are averse to trimming the crop sprouting from their ears as they are considered a mark of prosperity. We remember, as a lad of 11, being castigated by a rather severe looking Parsi tailor called Jassawalla, who had his shop on the top floor of the old Bombay Stock Exchange building, for not standing still during measurements, as we bent forward to curiously examine the rich clutch of hair emanating from his ears, long enough for a tiny plait to be weaved. He was an authentic Parsi eccentric. After a cardiac episode, he used to climb the staircase backwards, in this building without an elevator, and in the process, fractured his femur.

An overwhelming number of Parsis constantly twitch and tick. A leading cardiologist, kind and affable, boarded a domestic flight in the USA to attend a medical conference. His fellow passengers summoned Homeland Security to forcibly evict him as he was behaving suspiciously. All that the good doctor did was to constantly touch his forehead in sudden jerky movements, a twitch from childhood, which terribly unnerves his new patients. Like neuroticism and breast cancer, the community has a grossly disproportionate number of twitching and ticking Parsis. We had a paternal grand-aunt, who must have been extremely pretty in her hey day, suddenly contort her face as if she had just swallowed half a glass of unrefined castor oil. In those days of formal matchmaking, this must have upset dozens of prospective suitors, forcing her to marry our uncle, who looked like a cross between Dr Spock and R2-D2, apart from being rather dark complexioned, and which resulted in some wags uncharitably saying that kaagro dahitroon lai gayo (a crow snatched a delectable piece of baked yoghurt sweet).

To generalize unscientifically, most Parsi men have a rather kind and benign look of helplessness about them (save and except when they are debating some utterly irrelevant point at a meeting of the Federation of the Parsi Zoroastrian Anjumans of India, when their facial expressions resemble the early onset of dementia); while the ladies appear imposing and those who cannot be trifled with. Parsi ladies approaching the 40s have a general look of disapproval about them. You often find them snorting or gently placing their index finger on a nostril and inhaling lightly; as if they were doing pranayama (breath control). Some of the aggressive ones flail their arms in an exaggerated fashion, as they stompingly march with a penetrating Medusa-like gaze. There are, of course, angelic ones who neither twitch nor tick. Just a few days ago, we had a business meeting in the foyer cafe of a hotel. Three gents with us, all non Parsis, observed that there must be a big Parsi function somewhere in the hotel, as dozens of Parsis were relentlessly passing by. Pray, we asked them, how do you know that all these people passing by were Parsis. Come on, one of them guffawed, how on earth would anyone not recognize a Parsi. They are from a different planet.

Berjis M. Desai is a lawyer in private practice and a part-time writer. He considers himself an unsuccessful community activist.