The Solicitor

Berjis Desai

Although he was a litigation lawyer, he never left home before 10 a.m. Although he could afford a Mercedes, he leisurely self-drove a Morris, window rolled down to let the smoke, emanating from his perennial pipe, escape. Although many clients waited anxiously in the reception of his Pickwickian office in the Fort, he always first visited the Ripon Club, for some black coffee and dry toast. None could bother him on the cell phone, as he did not possess one.

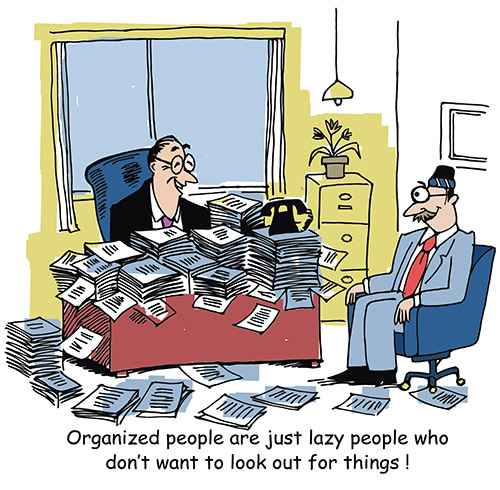

Unhurried and relaxed, he walked past some really nervous clients whose matters had already begun to be heard in Court, joking with a cluster of friends who had already occupied the chairs in his cabin, around a huge wooden table — 12 ft long and 4 ft wide. Not an inch of this table was visible. He was a fairly large fellow, but when he sat down on his swivelling chair, he was hidden behind a mountain of papers, counsel briefs, memos and title deeds. Ever since he had occupied this cabin as a junior partner of his father, he had never once cleared his table. He had this uncanny ability to shove his hand in a sheaf of papers and fish out exactly the document he was looking for. Almost like magic. After all, wasn’t he a kid having fun with the law?

His interest had to be aroused before he would accept a case. Fees were utterly inconsequential. Very conscious of his blue blooded origin, he found lawyers canvassing for work to be vulgar and crass. Clients, mostly well-heeled Parsis, sought his advice and strategy. After the dual system (advocates and solicitors) was abolished in 1976, and solicitors were allowed to appear in court, he began to argue. He possessed a decently sharp legal mind and a good command over the language. His integrity was spotless. He was eccentric alright and he was slow as a snail in delivery of work on time; yet clients remained loyal to him over the decades.

Illustration by Farzana Cooper

He loved appearing pro bono for Parsi charities, matters concerning the election scheme of the Bombay Parsi Punchayet, interfaith married Parsi ladies and other liberal causes, fire temple properties, and for his large circle of admiring friends. In any event, even those whom he charged, would receive his bill months later (if they did not pay, he never sent reminders).

He loved to poke fun at the opposing solicitor. "From a firm of your antiquity, we expect a more erudite understanding of the law. Even a first year law student will not advance such a ludicrous proposition,” he wrote to another law firm. Enraged, that law firm advised him to exercise restraint in correspondence. "Restraint will be exercised, when restraint is earned,” was his curt reply.

A spartan late lunch at the Ripon Club with a couple of his longtime non-lawyer buddies (one was a maker of Parsi headwear). Some more late afternoon fun in court. Walk down to the then famous Marosa restaurant to wallop the famed chicken patty or mutton samosas. Back in the office, he would himself type on a Remington (later, a computer) and seldom used a stenographer.

Judges knew him socially, tolerated his rather long winded arguments and his odd sense of humor. Once he told a junior judge unable to appreciate the nuance of the argument he was advancing: "My Lord, do not be so perturbed. Benches with far greater intellect have grappled too in understanding this proposition.” Luckily for him, the judge, from a vernacular background, failed to understand the backhanded compliment.

He would suddenly peer intently at the pocket of the uniformed peon of the then largest law firm – Mulla & Mulla & Craigie Blunt & Caroe – and read out aloud the monogram: "Mulla & MC & BC.” Although he was equally at home with Parsi aristocracy and hard-nosed "haandas (louts),” he did have a prickly ego and hated being outsmarted. While he was lucky with his Parsi partners (one partner senior to him droned in court with his eyes tight shut, until he was commanded by an irritated judge, to open them), he was outsmarted by a sharp, non-Parsi partner, whose shenanigans became the stuff of legend and began to impair the firm’s reputation. Our hero quickly parted company and preferred to have a truncated, rather than a compromised, firm. As a price for the separation, he had to undergo the pain and humiliation of giving up the 150-year-old hallowed name of his law firm.

Then one day, his longtime junior, madly in love with a beautiful colleague, convinced him that his table had to be cleared and the papers neatly classified. In a weak moment, he agreed. The junior and his beauty finished the arduous task on a Sunday after much coughing and sneezing from papers untouched for decades. Seeing the ancient table clean and empty must have triggered a moment of great passion, which they rather imprudently succumbed to just as our anxious hero, disturbed terribly at the thought of his paperless table, made a surprise entry into his cabin and was shocked to witness the beatific vision. Somehow this episode must have amused him, for he took no disciplinary action (however, half of Ripon Club soon knew of the salacious details). A few years later, the junior died young.

As he completed his enjoyable innings of 50 years as a solicitor, things began to change around him. Complexities of legal practice increased manifold: new law schools spawned a fresh breed of young lawyers; antiquated law firms began to fall by the wayside; aggressive new law firms began calling the shots. There was no space left for anyone as laid back as our solicitor. It is no longer a noble profession; it has become a business, he grumbled. But, he was a Prince and a Prince will never condescend into the market place. He was not anxious if clients were lost to the more efficient competition. His non-paying old-timers and hangers-on kept him occupied. They felt comfortable only with the ancient paper covered table, drab and stolid (barring those brief moments of amor); they were ill at ease in glitzy, electronically operated conference rooms of the large law firms. This was his constituency and he was their hero. He continued to argue cases but the newer, disposal-minded judges had no patience for an old man cracking jokes; and they began to snub him. Marosa had closed down long ago. Several of his Ripon buddies had perished too.

His inseparable pipe took a toll on his lungs; he fought gamely against cancer and remained active though feeble, hiding all kinds of personal anguish behind his perpetual grin. He may not have been scintillatingly brilliant, but he was sharp, in a good sense of the term as applicable to lawyers. He noticed at last that time had lost its leisurely pace, and had become frenetic. You could no longer roll down the window of the Morris and puff away at 10:30 a.m. You had to exercise restraint in correspondence, and restraint in everything else too.

Berjis M. Desai is a lawyer in private practice and a part-time writer. He considers himself an unsuccessful community activist.