Sister act

Berjis Desai

The new column "Unforgettable Ba-was” will unveil Parsi profiles.

They could not have been more different, yet it was a Sister act. One was large, dim-witted and innocent; the other was sexy, shrewd and sarcastic. If they were fillies, none would have believed that they shared the same sire and dam. In Bombay, they thought they were living in Dorset; and when in Poona, in Hertfordshire. How could the natives change the name of the city that their direct lineal ascendants had so painstakingly constructed brick by brick? Their pedigree was exquisite and their lineage impeccable. Born a decade after their King, George V, had landed at the Gateway of India in 1911, the sisters were tutored at home by a German governess, which accounted for their slightly guttural accent. They lived and died in a palatial mansion which sprawled over three acres in the heart of South Bombay. To rival it, there was a verdant wonderland in Poona and a cliff hugging one in Matheran.

When they were being amused by a bevy of ayahs (domestic help) and fed English gripe water, one M. K. Gandhi was being transformed into Mahatma Gandhi. British goods were being boycotted and millions wore khadi, spun on a handloom, which became the symbol of protest against the British Empire. English corsets, French frills and Chinese silk were to be replaced by the coarse khadi. Preposterous! Madam Bhikaiji Cama, also aristocratic, who had her inheritance confiscated by the British for her prominent role in the independence movement, was disloyal to our King and certainly not a role model for us, said the sisters. Decades later, during Indira Gandhi’s Emergency, the income tax raided the sisters, and were amazed at the numerous portraits of the English sovereigns. Upon being asked why, the impudent sister curtly said that "we do not recognize your government.” And how could they have? Pernicious ideas of civil disobedience and self-determination did not enter their little cocoon where liveried butlers served shepherd’s pie on a 32-seater dining table made out of rosewood with that immaculate patina. The many grandfather clocks just kept time frozen.

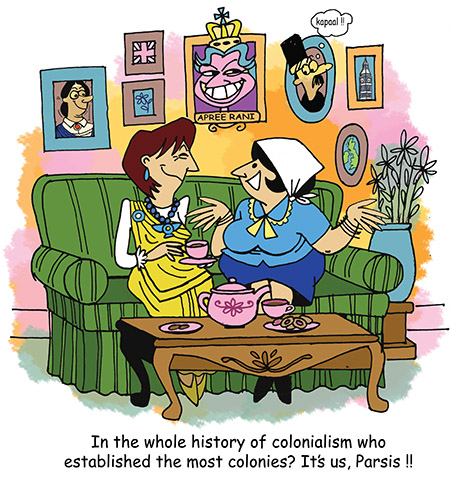

Illustration by Farzana Cooper

Their doting father, having unwisely invested in some textile unit, had frittered away ancestral wealth by importing red Buicks and large Chevrolets, an iron gate from France, to be seen later in The Sound of Music and several Stradivarius violins and grande pianos. Death rescued him from possible insolvency. Fortunately for our heroines, income from private family trusts created by grandparents on both sides, sustained their lifestyle of exotic single malts, retinue of servants at all three of their residences and the European sojourns on the Orient Express with royal suites in Parisian hotels. At least, for a while. Then, draconian wealth and income tax, estate duty, dwindling returns from insipid trust investments and fiscal indiscipline compelled them to sell the forest fairyland in Matheran to a non-Parsi hotelier ("who bastardized our bungalow”) and then the verdant woodland in Poona to a family of industrialists ("who replaced our Scottish wooden flooring with some Rajasthani marble from Hindu temples and installed a swing in the center of the living room”). Indeed, what could one expect from these nouveau riche with no class.

The larger one rode horses, recited dohas (couplets) from Kabir while simultaneously walloping succulent ham omelettes wrapped in ghee laden rotlis, saved the lives of stray dogs and was a mean cook of fluffy pastries; the younger one used her charm to ensnare quite a few of either sex and was proud of her good looks. Alas, like all mortals age was soon upon them and the tropics were rather unkind to their complexion. Unwittingly embroiled in litigation with their co-trustees in a public charitable trust founded by their ancestors, they spent much of their time in the Pickwickian offices of senior Parsi solicitors and chartered accountants. Accompanied by a couple of peons carrying a huge straw basket containing material for a proper afternoon tea — a Wedgewood teapot, tea cozy, half a dozen ultra-thin bone China cups, saucers with silver spoons, several thermoses and flasks, plates to eat very thin cucumber sandwiches along with scones and clotted cream (unfortunately, Parsi Dairy, not Devonshire), a bottle of cologne water which was liberally applied on their humungous sleeveless arms by an accompanying Parsi sidekick whenever an impudent mosquito dared to draw their blue blood, and a battery operated table fan to cool their erratic metabolism.

They enjoyed trading insults with the opponent co-trustees including those from their family and wrote the most original remarks in the minutes book of the public charity about the alleged sexual proclivities of their opponents. They defamed, and were in turn defamed, until a Parsi judge of the Bombay High Court went ballistic upon reading the minutes book which had a rubber stamped remark often in the margins like ‘Utter drivel’ or ‘Complete rubbish.’ At dusk, the elder one prayed from a prayer book in English, as the head ayah moved in the house with a lobaan urn (burning sandalwood and frankincense) more to ward off mosquitoes than propitiate the holy fire. Unable to travel abroad any longer (if no first class or limousines, then better not travel), they would request friends to get them some rare whiskey, and did not understand how a bottle cost £ 150 when Papa used to buy it for three-and-a-half shillings.

Unable to digest that their palatial mansion would be inherited by an obnoxious nephew, whom they detested, after they had passed away, they attempted to unsuccessfully disinherit him by obtaining an expert opinion from a High Priest (‘interfaith is adultery’ fame) that keeping a Muslim girlfriend was equivalent to an interfaith marriage. They fought many such Don Quixote battles including trying to prove that their eccentric brother, who perished within a month of his late second marriage, was poisoned (the only evidence being the brother’s own statement at a seance). Fearing a similar fate for themselves, the younger one warned her elder sibling not to partake the gourmet food deliberately laid on the table by their opposing trustees who knew the great weakness of their chairperson for such food. After a couple of hours of difficult restraint, the elder one, bored of the stormy meeting, would polish off plates of pastries, much to the disdain of her sister.

While they did not exactly love each other, they did manage a peaceful co-existence and a common front against those who betrayed their confidence. As Bombay became Mumbai and Poona became Pune, and Hertfordshire seemed so distant now; death conveniently intervened and they died within three weeks of each other. They survived quite well so far away from the Empire whose loyal subjects they remained and, despite such hostile native surroundings, ensured that they never fully connected with reality.

Berjis M. Desai is a lawyer in private practice and a part-time writer. He considers himself an unsuccessful community activist.