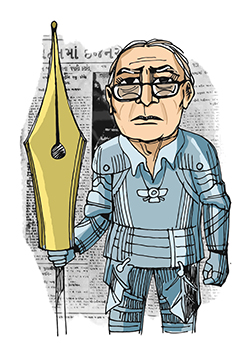

The editor

Berjis Desai

He boiled some tea leaves, added milk and sugar and handed over one cup to his ailing wife, the love of his life. Cursorily glanced at The Times and the Jam-e-Jamshed where he worked part-time every evening to supplement his measly salary as an officer in a nationalized insurance company. He ate porridge and a banana for his unchanging breakfast, walked from his tiny 480 sq ft home on the outskirts of the Dadar Parsi Colony to the BEST bus stop. Sometimes, he hired a black and yellow taxi. Ordinariness sat so comfortably on his brow.

Soon he would retire from the corporation he had steadfastly served for 35 years, barring a sabbatical for a year-and-a-half in Tehran to carry out research on the Persian language on a scholarship he had earned. His savings were grossly inadequate after his wife’s frequent hospitalization, and educating his two children. The son, though a qualified chartered accountant, was immersed day long in occult literature and acquiring encyclopedic knowledge of Aurobindo, Blavatsky, Alice Bailey and the Masters of the Great White Brotherhood.

Illustration by Farzana Cooper

After retirement, the father had to find a job soon. Honesty was his only god. Borderline agnostic, he did not pray or visit fire temples and was skeptical of his son’s belief in the afterlife. His calm, Buddha like bespectacled face revealed not a trace of his inner worries. He was soft-spoken to the point of being inaudible, though his eyes radiated power underneath those exceptionally thick and bushy eyebrows. From his school days in Ahmedabad, he had never fallen prey to anger or greed or lust. No passion excited him and laughter seldom shook his large frame. Many, including his son, thought he was a cold fish. Dutiful, intelligent, honest, proper, blemishless but a lifeless, boring, unexcitable stoic.

At his farewell function, he was gifted a HMT wrist watch. After several uncomfortable months of sitting at home, one morning he received a call from the owners of a venerable Gujarati newspaper which had a tradition of appointing only a Parsi as editor. The then editor, diagnosed with terminal cancer, required a replacement. During the interview, the owners could neither decipher his Sphinx-like face nor hear a word of what he was mumbling in his unusually low pitched voice. Honest Parsi with a working knowledge of Gujarati. Adequate for the job, concluded the owners. Within weeks, from a nondescript development officer of an insurance corporation, he had become the chief editor of a prestigious newspaper. The spotlight had fallen on the clapboy.

He began by dispassionately evaluating his strengths and weaknesses. He did not have the ability to write fluently in Gujarati (his predecessor-in-office was a noted Gujarati poet and author, with more than 30 publications to his credit). His evening stint in the Jamé hardly qualified as journalistic experience (the only memorable event that had happened there was that he had been propositioned by a widowed Parsi lady politician which had shocked him out of his wits). Again, his predecessor had over 35 years’ experience as a working journalist. The cynical veterans of the editorial department thought he was, therefore, easy meat. A softy Bawaji without the ability to navigate the world of Gujarati journalism. Ironically, he had been recommended by the same lady politician who had unsuccessfully propositioned him.

His first six months in office strengthened his subordinates’ impression that he was an innocent abroad. Although his salary had tripled overnight, his lifestyle underwent no change barring that he began travelling by taxi and ordering decent lunch from a Ratan Tata Institute outlet selling Parsi delicacies. During this period, his intelligent and shrewd mind objectively assessed the situation. He began to understand the mindset of his readership. Their hopes, aspirations, fears, likes and dislikes. He commissioned columns on municipal and local issues. It may not have been brilliant journalism but it touched the chord of the common man. And who understood the man on the Virar local better than him.

He could patiently listen for hours without uttering a word, with that mysterious smile on his expressionless face. Many who came to misguide were unnerved by his dissecting gaze and ended up blurting out the truth. He had not a single friend and never socialized. He was never a member of any club and he took no vacations. His wife was his only confidante and sounding board. The apple-polishers and hangers-on soon realized that they had no place. He received inputs though from unexpected quarters, with his uncanny instinct of knowing whom to trust.

And then, his focus shifted to Parsi affairs. His conscience was shocked by the alleged tales of nepotism, corruption, arrogance and inefficiency in the workings of the community’s charity trusts including the Bombay Parsi Punchayet (BPP) whose then satrap was the formidable B. K. Boman-Behram (BKB). BKB tried his old trick of turning on the charm taps on the unsuspecting editor, pooh poohing all complaints as motivated and baseless. He was heard with great patience. The editor began meticulously gathering firsthand evidence from Parsis he met. He converted the weekly column from Gujarati into English. His empathy for those suffering made his pen sharp, acerbic, sarcastic and carping. Facts were presented with the skill set of an experienced insurance assessor. Parsi readership of the Sunday edition grew exponentially. The satraps grew nervous from Saturday evening as to which bombshell would be dropped the next morning. The editor thoroughly enjoyed their discomfiture. They complained to the owners (who, to their credit, refused to interfere). They tried to induce him with the offer of moving into a large Cusrow Baug flat. It resulted in even more brimstone and fire. Week after week, he tormented the venal and the vain. His columns became a catalyst for a hitherto indifferent, very-thin-cucumber-sandwich-eating elite to form the CER (Committee for Electoral Rights) which radically reformed the BPP and swept to power in a landslide. He was the father figure of this movement.

His iconoclast self then commenced lampooning the diehard orthodox. Disposal of the dead, rights of interfaith married Parsi women and their children and excessive ritualism were topics highlighted in his columns. The orthodox hit back at him with equal vigor and venom in the Parsi media. By then, his image was too large and too reverential, to be tarnished. With a couple of other likeminded crusaders, he enjoyed the cut and thrust of these battles. Adrenaline had begun to flow in those ice cold veins.

From a nobody, he became an icon of Gujarati journalism. Recognition came fast and furious. Although he became a famous journalist and crusader, he continued to live in the same rented dark tiny flatlet on the ground floor. He never had a car or even a full time domestic help [at night, he warmed the bhona-no-dabbo (tiffin carrier) and served his wife].

At the time of his appointment he thought he would work for around five to seven years. He ended up working for 24. His wife passed away and his eyesight began to fail. The monopoly position of the newspaper was challenged by publications from large media houses. The owners wanted a more energetic editor. Polite, and then not so polite hints to exit were given. Somehow they did not register in his enfeebled mind. A couple of critical news stories were missed by the newspaper. He was summarily fired. He smiled, nodded, emptied his drawer, sat in a taxi and never came back.

Not wanting to be a burden on his children, he stayed alone. For nearly a decade. He died at 98 and was cremated. Emerging from nowhere, he had been an unlikely hero. He had galvanized an entire community. He had vocalized the pain of the poor. He had brought down the entrenched order. He had spurred reform. And that too, with innate humility and utmost simplicity. History will remember this servant of the Truth.

Berjis M. Desai is a lawyer in private practice and a part-time writer. He considers himself an unsuccessful community activist.