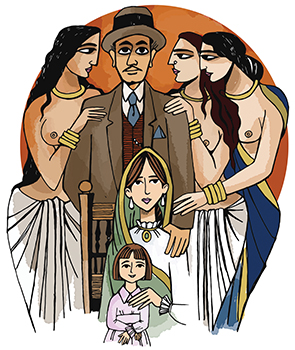

The illegitimate father

Berjis Desai

He hobnobbed with the maharajas, captains of industry, British rulers, his fellow lawyers, financiers and the pioneers of India’s nascent film industry. Being the son of a wealthy philanthropist and landowner in undivided India provided him with seed money and oodles of confidence. His tall and dashing personality, diplomacy, playboy charm and three-piece Savile Row suits made him the center of attraction. Here was a rare combination of brains, good looks, emotional intelligence, native shrewdness and ancestral wealth. God had bestowed on him everything a man yearns for.

When his father died suddenly at a Mediterranean port while on a voyage to England, the world seemed a calm and placid place. Within a week, however, Archduke Franz Ferdinand of Austria was assassinated which led directly to World War I. It was quickly decided that his elder brother would look after the family’s business interests in Karachi, while he would continue to manage the many landholdings in Bombay.

Illustration by Farzana Cooper

A qualified solicitor, he had been admitted when very young as a partner in one of the first solicitor firms of Bombay which had advised the East India Company and then Her Majesty’s Government in India. However, his entrepreneurial instincts were too strong to be straitjacketed within the narrow confines of the law. He instinctively knew how to multiply money. He expanded his family’s landholdings manifold. Shrewdly trading in property, he was cash rich and became a leading financier.

He was not exactly reckless though he was a risk taker. The business venture of a leading maharaja was falling apart due to lack of cash. He provided debt and equity to rescue the royal’s business empire and became his lifelong friend. The maharaja was a patron of the arts and introduced the handsome Parsi to a middle aged artist who was himself minor royalty. They became friends at first sight. One evening, in January 1901, the artist showed him some portraits which a century later, would make the artist world famous. The young man was mesmerized by the portraits of three young women, one of them topless. They are my muses, said the artist, they are from a devadasi family in Goa. Devadasis were girls dedicated as dancers to large temples and were deemed to be married to the gods. For obvious reasons, in a matriarchal society girls followed their mothers to become devadasis. They have European features, commented the Parsi. The artist complimented the keen eye of his friend. His muses were sisters and cousins with Dutch and Scottish blood. Azure blue eyes set in pink marble faces oozing sensuality.

During the summer court vacation, the artist accompanied the Parsi to Mapusa in Goa. The muses were more incredibly beautiful in flesh. They spoke Portuguese and broken English. The ladies could not resist the charming Parsi, so very different from the natives. Passion maddened the otherwise cold Parsi. He promised marriage to the eldest but ensnared the two other ladies as well. The women were no longer devadasis but free spirits leading a Bohemian lifestyle. When monsoons swept Goa, the elder one was pregnant. We shall marry soon, promised the Parsi. A son was born, and seven years later, a daughter. With the full knowledge of all three women, he sired children from the other two also. He looked after their needs adequately and was gentle with his consorts.

In the meanwhile, his stature grew by leaps and bounds in Bombay’s commercial world. He lent monies to one of the largest Indian industrial groups in distress and rescued them from bankruptcy. The satraps of the group became his lifelong devotees. In that era, gratitude was genuine. He became director of many companies dealing in textiles, electricity, steel and cement. His reputation as a shrewd financier was at its zenith. Corporate lenders sought his counsel; royalty wooed him. Marrying some devadasi from Goa was out of question. He was never really romantic, in any case. He married a dull Parsi lady from an aristocratic background.

The eldest consort in Goa was devastated. Within two years of the birth of their daughter she died, heartbroken. Without much fuss, he looked after the education of his four children, though they never saw their father from Bombay.

His Parsi wife bore him three children. He became obsessed with his eldest daughter — vivacious and ever smiling. The family alternated between Poona and Bombay. His hectic schedule, between board and business meetings, advising clients, lecturing to trade and industry, managing his ever growing real estate empire, was pleasantly punctuated by those tender moments with his little daughter who loved to ride her bicycle.

One Tuesday afternoon, when he was busy during some business parleys, they pulled him out to inform him that his favorite daughter had been killed in an accident while riding her bicycle. Instead of diverting his affections to his other six children, he became ice cold towards them. Mechanically, he discharged his obligations but seldom was a smile exchanged.

Strangely, he immersed himself more in trade and business like a relentless money making machine. When his children from Goa became adults and entered college in Bombay, he met them, one at a time, for a cold 20-minute conversation. Of course, their material needs were met adequately. His children from Bombay were always scared of him. They both migrated to America – one as a ballet dancer, the other as the wife of a Russian Count in a marriage of convenience. Both gently faded away from public gaze. There is a fascinating sub plot here, which we shall narrate someday, at an appropriate time.

His children from Goa were a different story. One became a prominent city dentist. Another, a crusading newspaper editor who wielded a fiery pen against the Indira Gandhi government. The third, married into a leading industrial family, was known for her immaculate beauty and led the life of a princess. The fourth rose to be the satrap of one of the largest business empires, like his father, a legend during his lifetime. He felt sad that his father did not live long enough to see his great success, having passed away one cold January night. He was just 56. In any event, he would not have been happy for his joy had been permanently crushed like the mangled tyres of that tiny bicycle in Poona.

Berjis M. Desai is a lawyer in private practice and a part-time writer. He considers himself an unsuccessful community activist.