The Brothers

Berjis Desai

Some 35 years ago, four Irani brothers in the restaurant and bakery business fell out and engaged four Parsi solicitors (your columnist, unfortunately being one of them) to litigate against each other. Their grandfather had migrated from Iran to India in the dying years of the 19th century and settled in Poona. Virtually penniless, he started a small bakery to make hard, round brown crusted white bread (brun pao). So hard that an inappropriately angled bite would make one’s gums bleed. Either you broke it and dunked it into a sugary milky concoction masquerading as tea, or liberally "Polson buttered” its slice ("brun maska with chai”). He was an honest workaholic and soon he had several bakeries in Poona and Bombay. George V visited India in 1911, which inspired his only son to start a tiny Irani café, somewhere in the by lanes of Byculla, called Kaiser-e-Hind Cafe, with ubiquitous black bentwood chairs, marble topped circular tables; the proprietor always behind the till, glowering at patrons who took too long to finish that little cup of horrific tea. He died young, leaving behind no will and four sons. The latter were perhaps the Kauravas of the Mahabharata reincarnated.

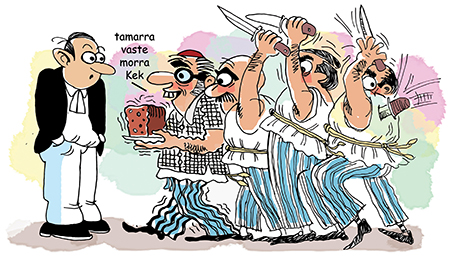

Our client was the oldest and nicest (relatively speaking), had Parkinsons and shook like a leaf. In the Bombay High Court, which they frequented, they dubbed him Dhoojto Irani (trembling Irani). All four of them were genuinely surprised to learn that solicitors actually charged fees. Upon seeing our podgy body, our fellow decided that we should be paid in cakes (baked by him, of course). So, we began to be inundated with cakes of all shapes and sizes. They were singularly ghastly. So much egg had been poured into the mixture that it was difficult to make out if one was eating a cake or an omelette. We would return from court in the evening, utterly exhausted and slump in our chair only to find some horrible cake or the other staring at us. Those days we had an old court clerk with an irritating whine, who would say, "Saheb, dhoojto Irani cake aapi né gayo! (Sir, the trembling Irani has left a cake for you).”

Illustration by Farzana Cooper

Early one morning, around six, our doorbell rang. Fearing that it must be the postman delivering an urgent telegram about the departure of a relative in Navsari, we looked through the peephole. We could only see a huge cake, bobbing up and down, violently. Our client, with a beatific smile, said: "Aajé mara bairi na varas chhè. Hoon tumaré maté khaas almond cake layaach (Today is my wife’s birthday. I have brought a special almond cake for you.)!” "It is 6:00 a.m.,” we politely reminded him. He vigorously nodded, "Yes! Yes! You don’t have to eat it right now.” Later, he haggled over our bill of costs, extremely low though it was, and after receiving a 50% discount, promised to bake more cakes for us.

His next-in-line brother looked a splitting image of Taras Bulba, the Cossack warlord, played to perfection by Yul Brynner in a movie released in 1962. In the April heat, Taras applied a ginger paste on his bald head. He did not have to jostle his way forward in a crowded courtroom. Most people readily gave way to avoid the unbearable stench of melting ginger mixed with the rancid odor of his perspiration. He spoke very little and understood even less. His bakery was next to the third brother’s, the most aggressive of the lot who released rats at night in Taras’ bakery. An enraged Taras retaliated by voluminously spitting into the Ratman’s dough, which was naturally not thrown away but baked into oven fresh pao, for which there was a beeline of customers. The Ratman gratuitously informed us that he placed the carved out half of a watermelon on his head to bring fever down, and had never used a towel in his life, after bathing.

The fourth brother was convent educated, suave and most devious. He forged an alliance with the dumb Taras to checkmate the other two. The Ratman offered to join our Mr Cake, who instead preferred to devise what he thought was a cunning strategy to divide and rule. Three of the solicitors had excellent rapport. They often met over lunch at the Ripon Club to narrate their respective client’s insanities and have a hearty laugh.

One evening our client looking terribly distressed, said, "Banoo (wife of Taras) had a hysterectomy performed by Dr Rusi Soonawala.” Our legendary patience was about to desert us, when he said, "Mara bairi boléch ké Banoo cannot get away with this, éné bhi potana hysterectomy karaavach (My wife does not want Banoo to have the upper hand; she too wishes her uterus to be removed).” We took a deep sigh, "What exactly is the relevance to this case?” Mr Cake angrily remarked that just as they were reaching a settlement, Taras had no business to upset the level playing field; and that we must speak to our good friend, Dr Soonawala, to agree to carry out his wife’s surgery.

Settlement continued to look elusive and the solicitors were unanimous that their clients wanted the battle to continue, just for the sake of it, as they were immensely enjoying its cut and thrust. One night, the smart brother’s brand new restaurant had a short circuit and burnt down. The fellow was ruined overnight. The three others rushed to his aid, hugged him, cried and made up. The consent terms were hastily tendered in court. Their wives, however, refused to smoke the peace pipe, which further united their once warring husbands. We readily agreed to waive our fees, to ensure that our fellow would stop bothering us. That did not happen. For years thereafter, cakes continued to come in steady succession. Even our secretaries and peons passed them on.

One Parsi New Year, we received an absolutely divine looking Black Forest cake, an exquisite product. It tasted great too. We were pleased that finally the Irani had managed to do it. We sent a thank you letter to him. His son, a rock musician who had no interest in baking anything, replied that his father had passed away months ago, leaving instructions that we must be sent a cake on every New Year. His father’s bakery had been sold, so he had ordered it from a five star patisserie.

Taras sold his bakery to the Ratman and migrated to Canada. The -30° in Toronto ensured that the ginger paste did not smell so bad. Ever since Taras had liberally infused the Ratman’s dough with his saliva, the latter’s bread sales had soared and every afternoon there was a stampede to grab the loaves. The youngest brother started a raunchy dance bar where stewards in suits shook your hand and served cucumbers and carrots with cheap whiskey, as inebriated customers showered Rs 50 notes on heavily made up dancing girls.

Berjis M. Desai is a lawyer in private practice and a part-time writer. He considers himself an unsuccessful community activist.