A different sort of head priest

Berjis Desai

A tiny town, almost a village, nestles on one of the most scenic beaches in Gujarat, about 38 km from Udvada village. Almost a century ago, when a vibrant Parsi community existed, it had, somewhat unusually, more athornan families and less behdins. In one such athornan family of small means, our hero was born. Blessed with a good memory and a sonorous voice, he was a natural candidate to emerge as a fully ordained priest from the Athornan Madressa.

In his late 30s, he managed to impress the trustees of one of the oldest agiaries in Bombay to appoint him its panthaky. A panthaky, in most cases, is not an employee of the agiary trust, but one who conducts or operates it, at his risk and cost. Within weeks, our ervad saheb ensured that this fire temple, then more than 250 years old, looked bright and cheerful. Its trustees were a motley bunch from the founder’s family — the managing trustee worked as an advertising manager with a vernacular newspaper and was an unbelievable miser; the other trustee, a dim-witted smiling giant, loved to be cast as a servant or a local idiot, in Parsi plays. Our friend was quick to tell his bosses that he would brook no interference from them in the running of the agiary. With a perpetual sardonic smile pasted on his rather handsome visage sporting a French goatee, the panthaky did not hesitate to dub his trustees, as ‘Sadantar ghelchodia’ [(‘SG’) the only original Parsi abuse (totally mad fornicators)]. For the rest of his life, he simply tolerated them.

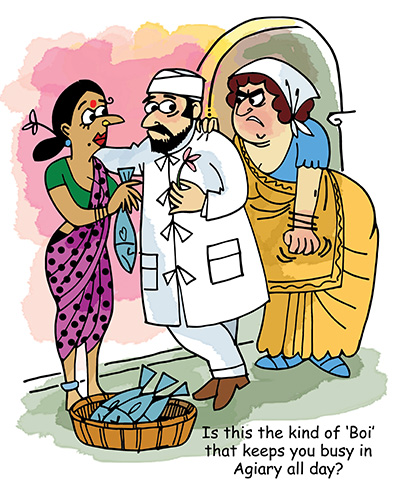

Illustration by Farzana Cooper

Ours is not a religion of abstinence. None is celibate; even the Prophet is said to have married thrice according to some texts. Good priests bring succor, solace and smiles; whether at a navjote, a wedding or a funeral, so long as they are not crassly commercial or seen as ‘babblers for money’ but display a passion for their job. They need not be orthodox or overtly liberal. They need not be learned or have mastery over the scriptures. Their job is to ensure that the worshippers feel like visiting the fire temple more often.

Our panthaky’s behdins loved him. Gone were the days when sickly looking priests listlessly droned the ritual prayers over apples which looked like lemons and malido which resembled cow dung. Aafringaans, farokshis and stooms were performed with gusto. The eagle eye of the panthaky would spot a laggard mobed dozing midway during a ritual who would soon receive a gentle kick on his rump from his boss. The behdins began to notice the enlivened agiary — brightly lit, efficiently managed; the quality of the chaasni (consecrated food) dramatically improved. The malido, enriched by egg yolk and dry fruits, made his clients salivate. The 18 days of muktad (venerating the souls of the deceased) saw a dazzling display of silver vases filled with roses and birds of paradise. The panthaky addressed the worshippers at the time of the culmination of the muktad — like a state of affairs address to the nation.

He would single out a bright mobed for praise or display his pride at one of his mobeds qualifying as a solicitor. Behdins became more liberal in doling out aashodads (cash gifts) to the mobeds praying for them, which subsidized their paltry salaries. Our friend encouraged retired employees who were navars to try their hand at being part-time mobeds. Many other of his part-timers rushed to their daytime jobs in Central Bank of India or Bombay House, just round the corner, at the stroke of 9.30 a.m., having prayed from six to nine, but not before gorging on a sumptuous sweet and savory breakfast prepared in the fire temple kitchen.

The head priest, married rather late, an Irani widow, double his size (she never used a towel after bathing, and in summer, cooled her head by placing a disgorged water melon cut in half; she could guzzle, without pausing for breath, a small pot of toddy). After the walloping she had regularly received from her deceased husband, she found the head priest to be a kind and gentle soul. Except for his die-hard gambling.

Around noon, when the bustling fire temple became quiet, the panthaky summoned one of his favorite chaasniwalas (agiary worker who home delivered chaasni to behdins), and pressed two tenners in his hand. "Today is Saturday, play on eight; the Chinese number,” instructed the head priest with a grin. Those days, a man called Ratan Khatri pulled out a number, every evening, literally out of a matka (earthen pot); and the number would go viral, by word of mouth, all over Bombay, within minutes. Payout was instant. The day our friend’s bet proved right, the boy would receive a liberal tip; otherwise, the priest would pepper him with the choicest abuse ["But, why are you abusing me, Saheb?” the boy would remonstrate; "Then, MC, (mother abuser) who else will I abuse — Ratan Khatri?” his boss would reply].

The local bank manager, a devout worshipper, lent money to the panthaky during a long spell when Khatri did not particularly oblige. In turn, the bank manager was allowed access to a room in the attic of the agiary, where a powerful Presence dwelled, and was sometimes even seen; the manager would light a lamp, recite a few Yatha Ahu Vairyos, and feel blessed. Until one evening, after indulging in some unclean activity, he visited the room without bathing; witnessed the wrath of the Presence and had to be hospitalized, with high fever. The bank manager too was then classified as a SG.

Not that our priest exactly abstained from unclean activities. However, he was an obsessive bather, followed by a kusti done with concentration and the sin was expiated. He managed a small Parsi orphanage in his hometown, which he visited often. The orphanage gave succor to many a destitute, motherless child. He employed a Parsi lady, also double his size, to manage the orphanage. His otherwise docile Irani wife did not take kindly to the increased frequency of his hometown visits. She made an unannounced trip and found the pair, not exactly managing the orphanage. (Our friend hardly knew English, otherwise he would have followed the example attributed erroneously to legendary lexicographer, Noah Webster, who stated, "My dear, it is we who are surprised. You are astonished!” when found by his wife in a similar quandary with his maid).

The head priest made no secret of his secular beliefs. He was a fervent devotee of Shirdi Saibaba, whose leading disciple was his guru. On the latter’s birthday, he organized a jashan in the agiary, for the guru’s Parsi devotees. He himself would lead the prayer, devotion dripping from his mellifluous voice. One of his senior full-time priests objected to this jashan for a juddin and was promptly sacked, after being peppered with some juicy epithets.

Jalaram Bapa of Virpur was a legendary Indian saint, with millions of followers, even today. Our head priest would not only attend the bhajan evenings at various Jalaram centers but himself play the manjira (cymbals), totally lost in blissful devotion. Like some other priests, he never bothered to go mufti, during such occasions. He went everywhere with full priestly regalia. When one of his orthodox trustees remonstrated that his extra religious worship was unbecoming of a head priest, he retorted by telling him that "you have no right to comment on what I do outside the agiary” (this is a censored version of the conversation). Despite his libertarian ways and liberal views, he only enhanced the reputation of the holy fire he so faithfully served. He skirted controversies and believed in gradual reform. Had he witnessed the antics of some of the present day priests — both radical and orthodox — he would have instantly classified them as SGs.

It is a matter of shame that the richest Indian community pays its practicing priests such paltry wages. Our panthaky, though not a spendthrift, liberally spent on travel and food. Like the way of all flesh, as age descended and his faculties dimmed, he could not manage his funds and began to borrow monies at extortionate rates of interest. Some imported injections which he could not afford could have prolonged his life. Too self-respecting to take help from charity, he preserved his dignity, all the way to death.

His agiary today, after many decades of his passing away, is perhaps the best managed in town. However, what is missing, is his style, his elan, his charisma and his colorful ways. The malido does not taste the same anymore.

Berjis M. Desai is a lawyer in private practice and a part-time writer. He considers himself an unsuccessful community activist.