Bombay was a different planet

Berjis Desai

Until 50 years ago, Bombay was a different planet for Nosaakraas, as Navsariites were called. There were three kinds of trunk calls — ordinary, urgent and lightning — which one could book through Bombay Telephones. Most were not aware of the third category which was used by newspapers, and a bit, by large businesses. Urgent, on an average, took about six hours to materialize. Too late to catch the Gujarat Express to be in time for Doctor Kaka’s paidast in the afternoon. Trunk calls were expensive. The telephone company man would self-importantly announce: "Navsari thi urgent call chhé. PP né aapo (There is an urgent call from Navsari. Give the phone to the PP)!” (PP meant Particular Person, a terminology widely used.) Then your uncle would excitedly talk; being connected to Bombay made him feel very important, as if he had just been appointed as spokesman for the Pope. Masi no gharaklo chaaléch (aunty has loud labored breathing before the imminent last gasp). So you packed your whites and took a taxi to Bombay Central Station, hoping to catch some nondescript train like the Viramgam Express. (We were once delighted to get into an empty compartment and were about to lie down on the dirty wooden seat, when we were told that the compartment was reserved for leprosy patients!)

You reached the moholla at dawn in a ghoraghaari (horse-drawn buggy) making a racket on the cobbled street, enough to drown the finale of masi’s gharaklo. The number of relatives who arrived from Bombay was a mark of status for the deceased and her family. Whether they came to mourn the dead or to celebrate six days of wedding gluttony, the paronas (guests) from Bombay were treated with great respect. Fali may have been a faltoo (loafer) on Foras Road, but he was greeted warmly as aapro (our) Framroze from Bombay. Most of the paronas were spongers who, in exchange for the Bombay pao (bread) and Polson butter, impoverished their hosts by gobbling up boi (mullet), doodh na (milk) puffs and khariya (trotters).

Navsari’s clock for religious ceremonies had two timings: Standard time, and Bombay time which was 40 minutes later. This created massive confusion. All the funeral notices in the Jam-e-Jamshed also stated Bombay time in brackets. Why Navsari, just 250 kms from Bombay, observed this 40-minute time difference is not known.

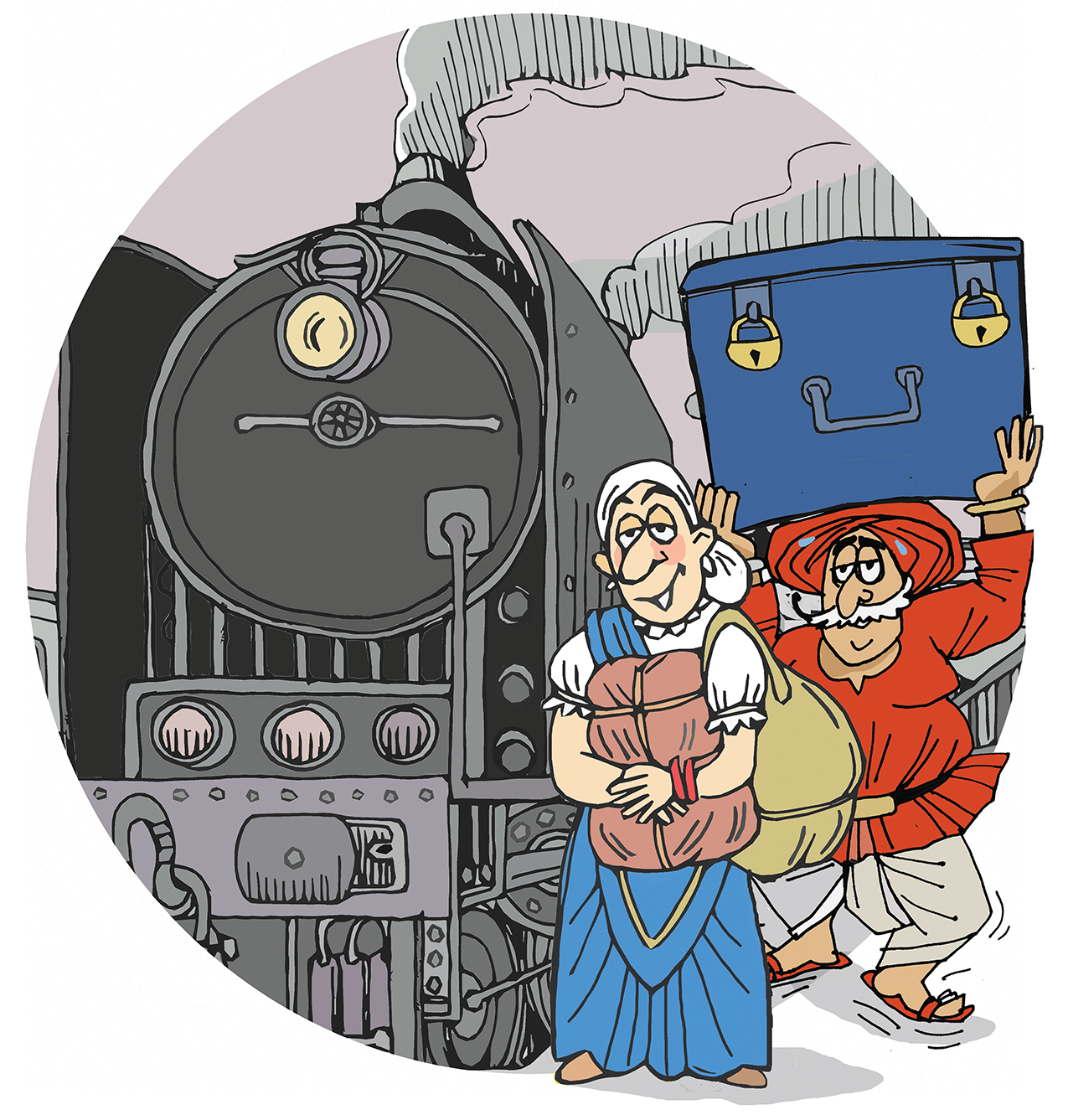

Illustration by Farzana Cooper

Traveling to Bombay was akin to space travel. Huge black colored tin trunks called petis were packed to the brim alongside the mandatory karandiyo, a large woven grass container tied with ropes, containing goodies generally unavailable in the city like sookka boomla (dried Bombay ducks), levri and levra (hard sesame toffees sprinkled with flour), boi, butter biscuits from Surat to be dunked in super milky tea, ghaaree (a sweetmeat laden with coagulated ghee, guaranteed to mess up one’s HDL-LDL ratio), raw groundnuts, lemon grass, Kolah nu achaar (pickle), papad and red cane vinegar. The karandiyo would be guarded like Fort Knox by the Parsi dowager who would not apologize if its contents dripped on some unfortunate darwand’s (a lower form of juddin) head.

The entire moholla would be excited at Soonamai’s forthcoming trip to Bombay. In those days trains halted at Navsari for three minutes and there was a mad scramble to deposit Soonamai, her tin trunks and karandiyo in an unreserved third class compartment, packed with hostile passengers glaring at every new entrant with undisguised hatred. Quarrels were frequent but quickly resolved over a cup of shared railway tea. The red turbaned coolies were perpetually dissatisfied with their remuneration and would argue until Bilimora station, even after receiving extra payment. At the Bombay Central station, several cousins who had taken casual leave from the Central Bank of India would receive Soonamai — and take away the goodies from her karandiyo which would be opened right there at the taxi stand, oblivious to the traffic jam this was creating.

The visiting guests would be fascinated to see the hosts cutting their nails with a small pair of scissors (nail clippers had not yet made their appearance); Burjorji Uncle from Seervai Vad, who had catered lifelong to British soldiers in Bareilly Cantonment, would use his faithful pocket knife instead. This columnist shed much blood from his nervous fingers and dreaded the pocket knife; Burjorji used to contemptuously say: "Nakh kapaavtaa étlo biéch, tau Army ma su karsé (If you are so afraid of cutting your nails what would you do in the Army)?” We could have told Burjorji that we would not be going anywhere near the Army.

Soonamai was very uncomfortable with the telephone receiver as if she was in dread that the caller at the other end would nibble at her ear. Navsariites seldom said "Hello.” It would be more like: "Ai Pavri nu ghér ké (Is this the Pavri home)?” confusing Sakubai at the other end who would say "Wrong number” and disconnect.

Back in Navsari, Soonamai would recount with distaste that three of Rusi’s immediate neighbors were Sindhis and the lone Parsi neighbor smoked a cigar. Her listeners would laugh uproariously when told about her discomfiture at the Greens Hotel (where the Taj Intercontinental stands today) while eating a huge cream laden pastry with a fork and knife. (While accompanying her, unsure of my ability to handle the cutlery, I lied that I had diabetes though I desperately wanted to eat a pastry too.)

Bombay Navsari na jooti é bi nahin aavé (Navsari is far superior), they would conclude, safely ensconced in the warm cocoon of their own ilk, simple but superior, where Parsis were the ruling elite. Not knowing then that the coming forces of inexorable change would make Navsari cosmopolitan, even more so than Bombay. The vads would be invaded by strangers but the baugs of Bombay would retain their Parsi-only character. At least, for some time more.

Berjis Desai, author of Oh! Those Parsis and The Bawaji, occasionally practices law.