Just the other day, this columnist was stunned to learn that there are only around 37,000 Parsis in Bombay. Our community institutions are increasingly inefficient and crumbling. The so-called leadership is a combination of prickly egos, enlarging prostates and diminishing minds. Most Parsis are utterly indifferent to the fate of the community. This atmosphere of doom and gloom may, perhaps, be dissipated by discovering the magical aspects of our religion. A religious revival may then trigger a socioeconomic and demographic revival.

Zoroaster was one of the greatest prophets, his faith is replete with many magical qualities. Most of us find little meaning in mechanically reciting prayers in a language which we do not understand. While there is much to be said about the manthric vibrations of the prayers and the spiritual energy they unleash, the indifferent require to be enthused with some magical results. Color has to be infused in humdrum rituals, rites and recitations. We have to raise the rhythm of our spiritual practices.

Much is written in occult and theological literature about the Lost Word. The Rosicrucians and the Theosophists believe that the Lost Word is to be found in the Avesta prayers of the Zoroastrians. Recite the Lost Word with concentration and a clean heart for creating positive energy. It also acts as a shield against negative or malevolent forces. This word is oft repeated in several of our Yashts. The Rosicrucians teach as to how each syllable of the Word is to be recited on each day of the week, for awakening the chakras or psychic centers in the body.

Sufis, members of the only esoteric sect of Islam, believe that the continuous recitation of any divine phrase or name, like ‘Allah’ is highly beneficent. They call this practice ‘Dhikr,’ literally, remembrance; akin to the tradition of counting rosary beads among Catholics or chanting ‘Hare Rama, Hare Krishna’ or ‘Om Namah Shivaya’ amongst Hindus. Reciting the Lost Word or one of the 101 names of Ahura Mazda, in similar fashion, is a practice well known to Zoroastrianism. According to legend, the Prophet was assassinated whilst praying with his beads in an atash behram, his last act in life, which underscores the importance of this practice. Our grandmothers prized their kerba ni mala (rosary of amber stones) known throughout world cultures for its many magical properties. Many miracles are associated with the intonation of the Ahunavar or the Yatha Ahu Vairyo capsule prayer. Chanting the Lost Word with a kerba ni mala can manifest dramatic results.

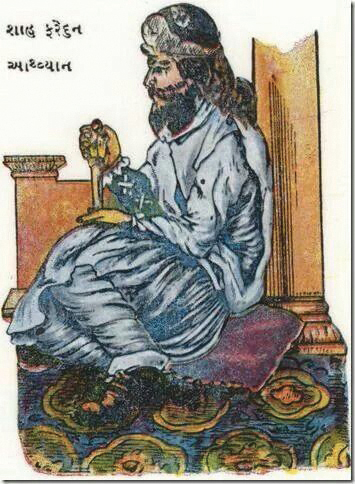

After Zoroaster, the most powerful magician — healer — king was Shah Faridoon, composer of an extremely potent nirang (prayer) to ward off disease, black magic and despondency. The little blue booklet containing this prayer, in Gujarati, was published many decades ago and is a collector’s item. You grasp the right hand thumb of the afflicted and intone the Nirang, with the oft repeated potent formulae — Fè namè yazad, ba farmaane yazad; baname nik Faridoon e gaav daye.’ This columnist has witnessed some amazing things which confound rationality.

The daily rituals performed in an agiary only interest a micro minority. However, many even with a faint interest in religion, will throng to perform a personalized ritual like lighting a divo at the Bhikha Behram well and making a wish; or seeking a cure for sunstroke or jaundice or migraine or piles, through recitation of Zoroastrian prayers; or be counselled spiritually by someone like the late Ervad Nadirsha Aibara of the Cusrow Baug Karani agiary.

The hard-core orthodox are doing their cause a disfavor by writing and speaking on esoteric issues in a highly pedantic style. Few will come to attend a lecture by a 90-year old at the Bharda New High School, at 4.30 p.m. on a Monday, on the "Significance of Varasiaji in post-Zarthost Cosmology.” They further put off people by expressing rabidly communal, sexist and nearly fascist views on ethnic superiority and the like. If their energies are utilized to share esoteric knowledge, as a solution for daily issues, many can be made to take interest in community matters.

According to Theosophists, the Prophet, like other great initiates (Rama, Moses, Orpheus), has an aura, wide enough to fill half a country. Interlocking your mind in his great consciousness, for selfless reasons, can inspire you to do something for the community and the religion. Aspirants on the path often carry out visualization exercises at dawn like Zoroaster’s radiance lighting up their home or workplace; or praying near the sanctum sanctorum of their favorite fire temple, as if they were physically present. Such simple spiritual exercises enable the practitioner to raise the consciousness of those around him. The universality of the Prophet’s teachings can break down artificial barriers and pave the way for reform. The stranglehold of the fundamentalists over community institutions can be broken if the hitherto indifferent are inspired to serve.

The situation demands unorthodox methods to revive the interest of Parsis in their faith, and through it, in the community. The rationalist must learn not to dismiss everything as mumbo jumbo. If people visit the Banaji Atash Behram on Monday evenings or pray in a small attic room in one of the oldest agiaries in Fort, do not mock them. We require every ounce of interest and energy to generate a demographic revival, by all possible means. And, yes of course, the Lost Word is Mathrem (pronounced ‘Ma,’ short for mother; ‘threm,’ to rhyme with frame). Get hold of a kerba ni mala and start chanting.

Berjis M. Desai is a lawyer in private practice and a part-time writer. He considers himself an unsuccessful community activist.