The doctors

Berjis Desai

Both were born within a week of each other in the dying years of the 19th century. Many generations ago, they had had a common ancestor. In a narrow mohalla (locality) of Navsari, their homes faced each other. Both were practicing general physicians (GPs). One had a decrepit dispensary opposite the railway station; the other made house calls only. We shall call them Dr Fredun, an MBBS after six failed attempts, and Dr Eruch, an MD. The former was a workaholic and the latter a lazy lump. Classmates at the Grant Medical College of Bombay, they were mistaken as brothers due to their common surname. The two could not have been more different.

In 1930, when the Great Depression was raging in America, they commenced practice more or less at the same time. Dr Fredun resided with his two bachelor brothers and a spinster sister; Dr Eruch with his father and a sister, an unbelievably garrulous dwarf, whom the town had nicknamed Jam-e-Jamshed for her propensity to grill her brother for the most sensitive information about his patients and then relay it to all who cared to listen. In today’s times, she could have established an excellent medical transcription start-up.

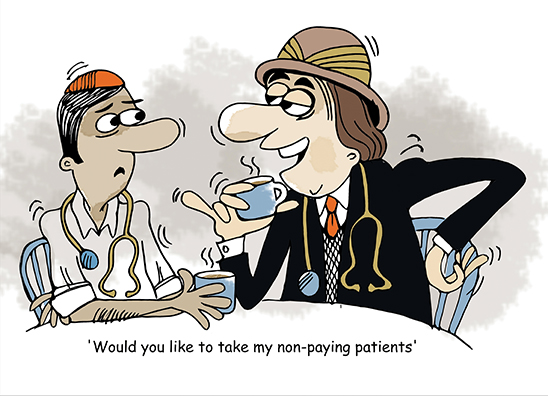

Illustration by Farzana Cooper

Dr Eruch had an exceptionally brilliant mind and a natural flair for diagnosis. His competitor’s knowledge of medicine was only slightly superior to his longtime compounder’s, in whose paramedical skills many of Dr Fredun’s patients had implicit trust. Despite this, Dr Fredun’s practice thrived while Dr Erach’s meandered. The former was a genial man who knew more compassion than medicine. He charged ridiculously low fees and at times tucked money under the pillows of poor and malnourished patients to enable them to eat well. He never charged practicing mobeds and their families. He would never remind a patient to clear any long outstanding dues. He liberally distributed free of cost medicines he received as doctors’ samples. After paying rent for the dispensary, his compounder’s salary, the cost of syringes and medical supplies and his long serving driver’s wages (for 30 years he used a Baby Hindustan which had no shock absorbers), Dr Fredun never made a farthing of profit. Fortunately, his brothers earned well enough to sustain their spartan lifestyle. The doctor served his patients with missionary zeal.

On the other hand, Dr Eruch’s astronomical charges must have caused many a myocardial infarction. He refused to even speak to a patient who had defaulted on fees. Quite bluntly, he advised those who pleaded for lower fees, to consult Dr Fredun. He doled out no freebies and had no employees. He refused to walk more than 200 meters and patients had to send him a horse driven carriage to bring him to their homes. His sister cooked, cleaned, washed, swept, brushed and acted as his housekeeper without a dime for her pains. Of course, in turn, she had to be regaled with patients’ secrets. Her mental grasp was slightly better than that of an orangutan. On one occasion Dr Eruch was summoned to dress a deep wound on a boy’s leg caused by a horse stepping on his ankle. Upon his return, Dr Eruch faithfully narrated to his vertically challenged sibling the gory details of the incident ["Ghora no pug, Minoo na pug oopar, jor thi paryo Minoo’s foot was stamped on with force by a horse)!”]. Soon the town was stunned to hear that Minoo’s foot had stamped the horse’s foot, causing a deep gash on the wretched animal. Soon legendary tales abounded about Minoo’s celestial strength and limitless sexual prowess. Some dimwit even asked the sister whether Dr Eruch had been summoned by Minoo’s mother or by the ghora gari walo (carriage owner).

During his long medical career Dr Fredun, a short, unusually dark complexioned man, always wore white duckback trousers and a white cotton bush shirt. The trousers were washed every week and the shirt every couple of days. Night calls were always made in sudro, legho (pyjama), kusti, topi né sapaat (slippers). The tall and handsome Dr Eruch preferred to dress in a three-piece suit and was never seen without a tie. His head was covered by a sola hat. He made no night calls. His neighbor never retired to bed without praying for half an hour, however dead tired he was. Dr Eruch, of course, had forgotten how to pray.

While in medical college, they were civil to each other but not cordial. After they commenced practice, the distance between them grew. Dr Eruch resented the concessional fees charged by his competitor. Dr Fredun was upset with the former’s carping comments about the lack of Dr Fredun’s medical competence and his appalling standards of hygiene ("single biggest reason for the reducing population of Parsis in Navsari”). And then, late one night while Dr Fredun was in Baroda, his sister suffered a severe asthmatic attack and Dr Eruch was summoned. This was one night call he could not refuse. The attack passed, but the patient fell hopelessly in love with the physician. Her brothers had no objection and approached Dr Eruch’s father with the proposal. A package deal, insisted Dr Eruch’s father; let the doctors marry each other’s sisters. "I am committed to remain a bachelor,” said Dr Fredun firmly. This greatly incensed the lady whose belated hopes of matrimony were rudely shattered. No deal on the table, was the response. The asthmatic sister, lovelorn, pined away and soon died. Whether of asthma or heartbreak, was not known. Both doctors remained bachelors. However, the short one continued to bear animus against Dr Fredun.

Decades passed, and nothing much changed in the sleepy town. In a strange way, both doctors grew fond of each other and often met over a cup of tea. Dr Fredun’s family had an ancestral vadi (a kind of farmhouse/orchard) at Lunsikui, where the venerable Sir Pherozeshah Mehta used to stay in the Dhadaka-no-bungalow whenever he appeared in the Navsari courts to fight some important case. At this vadi, every weekday evening, Dr Fredun met his friends for some lighthearted banter. Readymade tea was prepared in a huge aluminum kitli (kettle) and poured into glasses, in which large batasa biscuits were dunked and eaten with a spoon. On Dr Fredun’s birthday, chutney potato pattice from Mama’s (a legendary sweetmeat and savory snacks vendor), was added to the menu. Dr Fredun invited Dr Eruch to join the club, which he readily accepted. Dr Eruch came to secretly admire the silent humanitarian work of a not-so-great doctor who was a great human being.

Then, one night Dr Eruch was required to make another night call at his neighbor’s residence. Dr Fredun was writhing in excruciating lower abdominal pain. A severely inflamed appendix was the possible cause, thought Dr Eruch. Strangely, Dr Fredun was not willing to remove his clothes for the doctor to examine him. After much cajoling he did. Dr Eruch managed to remain expressionless on discovering that Dr Fredun had a rare condition called testicular agenesis. "I trust you not to divulge my condition,” pleaded Dr Fredun. Dr Eruch nodded. The next morning, Dr Eruch narrated the matter to his sister, not to satisfy her curiosity but to dispel her belief that she had been rejected wrongly by Dr Fredun. "He is a thorough gentleman. He did not want to marry you as he knew that he was incapable of fathering a child,” explained Dr Eruch. Within days, the entire town knew about Dr Fredun’s disability. Greatly distressed, Dr Eruch profusely apologized to his friend about the embarrassment he had unwittingly caused him. Dr Fredun smiled sadly.

Within months, Dr Eruch’s sister died, compelling him to request his nephew and the latter’s live-in partner to move in. The couple were followers of the Irani godman, Meher Baba, and organized bhajans (devotional songs) at home, despite Dr Eruch’s protests. This emotional upheaval resulted in Dr Eruch suffering a stroke and nearly losing his mind. To compound matters, the lady’s brother, a brilliant barrister, suddenly went insane. Dr Eruch’s bed was moved into the patio of the house where he shivered under a blanket in the cruel Navsari winter. Malnourished and uncared for, his large body developed painful bedsores. Like some bizarre tableau, on the ground floor, bhajans were sung; while on the first floor the mentally disturbed barrister conducted trials throughout the night, addressing an imaginary judge and jury. Dr Fredun could not bear to see the plight of his friend. He shifted Dr Eruch to his own bedroom and personally nursed his sores, oozing blood and pus. If Dr Eruch became delirious with fever, Dr Fredun applied cologne water swabs to his forehead and fanned him throughout the night. Somewhere deep within him, Dr Eruch knew what was happening. Although he could not speak, tears of gratitude rolled down his cheeks as Dr Fredun fervently prayed to Ahura Mazda for his dying friend.

Berjis M. Desai is a lawyer in private practice and a part-time writer. He considers himself an unsuccessful community activist.